An Ordinary Week, An Ordinary Town and an Existential Question

How much can you compromise nature?

Years ago, I had my astrological chart read by Arifa, a woman famous here in Maine for her uncannily insightful maps of, in her words, our “particular energetic archetypal wiring.” “Oh dear,” I remember her saying with what sounded like a little alarm in her voice, “it will be really important for you to stay in connection with your earth sign, Capricorn, because you have so many air signs that if you aren’t careful, you will be blown far into the clouds, far into the universe of ideas and ideals.”

I fear I have taken you, reader, on too many of these flights into the universe of ideas and ideals: into history and the ever expanding and mind-altering lessons it offers us for the present. Perhaps you feel, as I do, a little breathless, in need of a little rest, or of a small story of how these mammoth lessons of history show up in an ordinary week, in an ordinary life, in an ordinary town.

So I have a story for you.

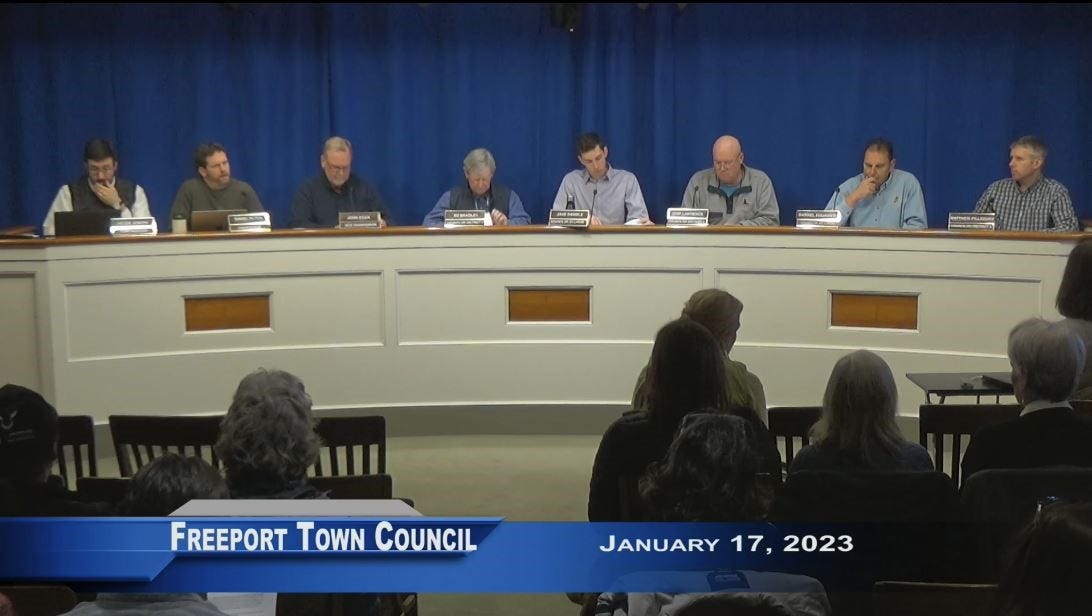

The story begins very unsuspectingly at a Freeport Town Council meeting on a Tuesday night not over two weeks ago. I go late to the meeting because the topic I want to support: a budget item for Meetinghouse Arts, is listed towards the end of the Council’s agenda. When I walk in, about thirty or forty people are already assembled in the room where the council meets, their winter coats thrown over the wooden chairs arranged in long straight rows that face the seven Council members and the Town Manager and the Town Clerk, all of whom are also in a straight row in their seats on the slightly raised stage. Every person on that stage, but for the Town Clerk, not visible in the picture below, is a man. Everyone in the room is white.

Off to the side, standing before a podium and a microphone, is a woman, deep into making a presentation. She has long brown hair and a calm demeanor born, it seems to me, from a deep understanding of the subject. I soon learn she is a member of the town appointed Conservation Commission and is reporting on their newly completed Hedgehog Mountain Management plan, a plan designed to assure that Hedgehog Mountain, a town owned property, would be preserved and used according to the Commission’s ordinance.

It was a little hard for me to hear her, and I kept asking the woman beside me, a once-upon-a-time neighbor and a state-wide expert in land conservation, what had just been said. Charts and graphics and lots of data about soils and trees and plant life were projected on a screen on the wall behind her, making it easier for me to grasp the many points she was making.

When you think mountain, think 308 feet above sea level. That’s how desperate we are here in Freeport for good views. The mountain is the highest spot in town, a place from which, after a short climb that doesn’t leave you out of breath, you can, on a clear day, see the real mountains in the west. Essentially, after extensive study, the commission was recommending that there should be no building of or use of mountain bike trails above 180 feet where the soils are very thin and would be dramatically and negatively altered, as would the plant and animal ecosystem.

The Conservation Commission ordinance prohibits:

activities detrimental to drainage, flood control, water conservation, erosion control or soil conservation, or other acts or uses detrimental to the cultural, natural, scenic or open condition of the land or water areas” and requires that the Commission keep its property “predominantly in its natural, scenic or open condition” (Section 35-5).

Ah! Mountain bike trails! Now I remember. The regional mountain biking association wants to build an extensive mountain bike trail on Hedgehog and has already raised money for the project. My grandchildren and daughter and son-in-law are mountain bikers and would, I am sure, love not to have to drive miles to find a trail. I look around at the audience and realize that there are many here who have come to support this effort.

Can you feel the tension in the story start to rise? Soils and plants and wide-canopied trees and soft furry animals versus the mountain bike? Eight men on a raised stage listening to a woman champion the case of nature.

The woman from the Conservation Commission finishes her presentation and sits down. A tall, straight-backed, athletic man rises and walks to the podium. He is the representative from the regional mountain bike association. I can’t help but think as he adroitly adjusts the microphone that if this were a graphic young adult novel, this man would be one of the heroes and he would be called Mountain Bike Man, or maybe just MBM.

MBM is accompanied at the podium by two small, adorable, tow-headed boys, his sons, he tells us. They will pull at his pants, hold onto his pockets and hide behind the video screen all the while he is presenting. He is quick to begin his presentation by reminding the council that two years ago his regional mountain bike organization was asked by a previous Council to present a proposal for mountain bike trails at Hedgehog in order to address the town’s wish to bring “growth” to Freeport.

If the town were to adopt this plan, he said, he could assure the town that the trails would be extremely popular, and people would come from all over the state to use them. He could also assure the Council that not being able to build these trails above 180 feet was of no interest to his organization as it was the trip to the top that would lure bikers.

Now we have all the ingredients of a real drama, a conflict that every town now faces: one side speaking up for growth, getting to the top, money; the other side speaking up for nature and balance; two small children, tugging. I can’t help but see this story in the light of all the themes I have been writing about: the violence and subjugation that adheres to ideas of growth, progress, individuality and entitlement. Only this time the victim is not Native Americans or Black men and women—this time the victim is nature.

The Town Council, I can see, is really in a bind. Two years ago, when the town was faced with so many closed storefronts, it asked for this proposal from the mountain bike organization. Since then, monies have been raised, but now their own Conservation Commission objects.

MBM’s presentation is smooth and reassuring. He doesn’t address the problems presented by the Conservation Commission: that the shallow soils at the top, only 6” deep, hold the wide and shallow root systems of the summit’s wide-canopied trees and if disturbed would likely lead to the death of these trees and other plants; that the soils sequester even more carbon than trees and their destruction would increase carbon emissions; that increased use would drive away the wildlife from this very unique piece of undeveloped land.

Instead, MBM focuses on the issue of erosion, giving us lots of data about how little erosion a well-designed and maintained mountain bike trail causes. I can feel the audience fall under the spell of his well-articulated arguments and his charm. Even his description of how trails are made doesn’t cause any of the councilors’ eyebrows to furrow.

We have machines, he tells us. Machines that are so well designed they create no harm to the roots or the plants or the ecosystem as they do their work. They dig down 6” and compact the soil so well that the trails will result in no run-off, no erosion. What happens when this machine is used above 180 feet where the soils are only 6” deep? No one asks that question, they are all spellbound by MBM.

By the end of his talk the Town Council members are totally flummoxed. They agree that both sides have presented a good argument and they have no idea whom to believe. “If this were a trail”, one of the TC members says, “I’d ask for an expert witness.”

There must be a way to find a compromise, they decide. Let’s ask both sides to sit down and see if they can find that compromise and come back in three weeks and report.

The meeting ends. Another compromise with nature is about to begin.

I go home, intrigued by images of this machine, the deus ex machina of mountain bike trails. I reflect ruefully on technology being offered as a way to save nature and get those mountain bikers to the top. I email MBM to ask him how this machine works, but never hear back from him.

Removing 6” of soil on 6 miles of trails would result, I am told by the conservationists familiar with this, one football field of earth 14’ deep or 240 dump trucks filled with dirt. And how do you get all this dirt down the mountain and where does it go and what harm will come to the creatures who depend on the soil: the lichen and the worms and the buried eggs of moths?

I am out walking in the trails through knee deep snow one afternoon this week when I emerge, wet and tired onto the dirt road and find my daughter and her dog hurrying to the bus stop to meet Addie. We are a little late getting to the corner where she gets dropped off, so we watch her, holding our breaths that she doesn’t fall, as she runs down the icy hill ahead of us. At the bottom, laughing and happy, she flings herself into our arms. She reports on the joys of eating a particularly good strawberry ice cream sandwich she spent money on at lunch and, no, she says to her mother, she hasn’t gotten the results of her math quiz back yet.

In the half second lull in conversation, I break in and ask, “Addie, you know Hedgehog Mountain, right?” She nods her head enthusiastically and recounts walks she’s had to the top and birds she remembers singing there. “What would you think if they built mountain bike trails to the top?” I asked her in a totally neutral voice, wanting her opinion to be uninfluenced by mine.

Immediately, her demeanor changes: her chin sticks out, her eyes glow, her voice rises and her speech comes out breathless and fast, rising and falling like the fast-running creeks full from the rapidly melting snow. She raises her arms towards the sky and shakes her head.

That would be terrible! How could they do that? Don’t they understand about the soils and how important they are to the trees and the plants and the wildlife that depend on all that? Don’t they understand what using a machine would do, probably it would be diesel and that would send poison into the atmosphere and that would make it harder for species to live and if one species died it would never come back.

I am floored. This eleven-year-old totally gets the cycle of life, gets the principles of ecology, the interconnectedness of nature, the fact that one more compromise with nature, no matter how seemingly small, could have devastating effects on life. “How did you learn all this?” I ask her. “I don’t know, I just pay attention.”

************************************************************************************************************

But I do not feel helpless or hopeless about this story. It is not over. There are things to be done here in this small town before any compromise happens. There are many amazing, wonderful people here who share my values and are willing to speak up. There are conversations to have, organizations to rouse to the cause of nature, facts to check, ideas about good growth vs. bad growth to toss about. And there are men on the Town Council will will listen to all this, and, I hope, decide that this one compromise with nature isn’t worth it. That our town, home to that big store that says we should all Be An Outsider, understands as well as Addie, that you can compromise with nature for just so long.

Another important tale. You are such a good storyteller, Kathleen! Addie is amazing!

So good Kathleen!