It is mid-afternoon almost two weeks ago when the Amtrak Boston train arrives and spits the four of us out into the dark bowels of Penn Station. The half-lit platform, the rusted metal tracks snaking into the black tunnels, the sour smell of dampness and dirt: all of it is immediately familiar. A rush of old memories runs in my mind like a YouTube video: A handsome, dark-haired boyfriend whom I meet for a date under the clock in the big station hall, before they tore it down, before he broke my heart. A trip to the City with austere Aunt Rosalie who takes me to Radio City Music Hall where the Rockettes dance in a long line of legs and ruffled skirts and I vow that when I grow up, I will become a tap dancer.

Then I see the newly hung sign that says Moynihan Hall and I am overcome with that lost feeling I have a lot lately, that feeling that everything that was once familiar is now unfamiliar and, furthermore, going too fast, rushing towards some meaningless point of oblivion. But with two grandchildren to shuttle twenty blocks north from 33rd and Broadway up to our hotel on 53rd I can’t afford to be lost or even look a little befuddled.

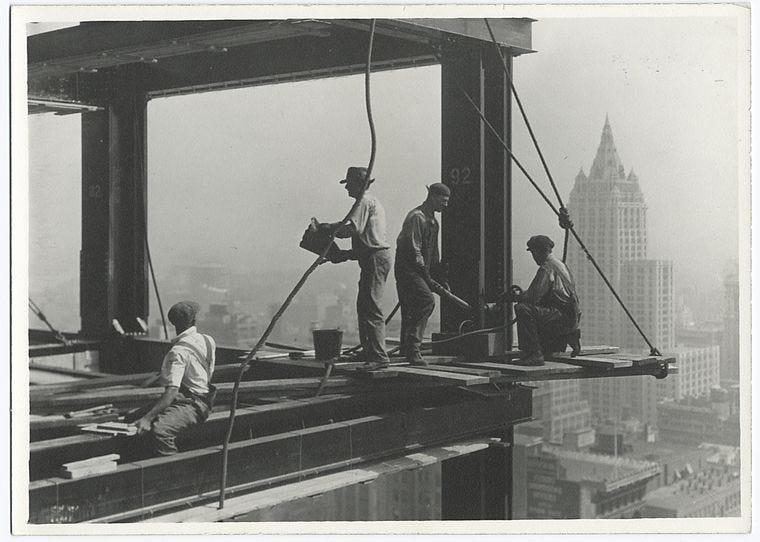

This is the city of my forefathers, and I am intent on summoning the spirits of my ancestors and teaching the grandchildren about our family’s history in this place called New York City, this place their ancestors entered as Irish immigrants, helped build till it scraped the sky, this place that gave them power and, too, took their lives and stole their hearts.

We are out of the tunnels and onto the street in seconds. Everything is moving as it always has been in this City that never sleeps, except this time, there are bicycles vying for space beside the cars and bicycles crossing the intersections with the pedestrians. “Can we take a taxi to the hotel, Gigi?” the kids plead. What real New Yorker would ever consider taking a taxi twenty blocks instead of walking, I think to myself. “Nope, this is a place where you walk, let’s go”, I tell them emphatically. I grip the handle of my wheelie suitcase, wait for the sign to say “WALK” and step off the curb.

It's cold here today, the wind that feeds on the canyons between hundred-foot-tall buildings whips at our faces. The sidewalks are crowded with people, some talking to real people beside them, but many laughing or in very serious conversation with invisible digital companions, their discussion seemingly so riveting as to render them oblivious to where they are and unless you keep your eye on them, I fear they will bump right into you and likely topple you to the ground.

We’ve been in the city for fifteen minutes and already I am tired and dreaming about a nap. The city that used to exhilarate me, now exhausts me. Halfway up Broadway, electric bikes hurtling by me at warp speed, the faces of the riders competently unreadable, their next move as unpredictable as snow is now in January in Maine, I am reminded of the fate of my own maternal great grandfather who was killed right here on the streets of Manhattan, run over by what was a new invention then: the trolley car.

I decide it would be a terrible idea to scare the grandchildren with that story now. But thinking about that grandfather makes me wonder what short story and essay writer and New Yorker, James Thurber, whose book, The Thurber Carnival, was on my nightstand when I was a teen growing up on southern Long Island, would have to say about this place if he were suddenly reincarnated, particularly about this harrowing experience of crossing twenty streets, each time having to decide if there’s time to cross before a car and now a bicycle reaches the intersection and mows you down.

Thurber was born at the end of the nineteenth century at a time when new technology was upending the old world, and a new world was being born. Much of his writing was an attempt to make sense of the modern world and, even as this story, written in 1937, “Sex Ex Machina”, reveals, to make sense of the act of crossing the street!

The story opens this way:

Sex Ex Machina

With the disappearance of the gas mantle and the advent of the short circuit, man's tranquility began to be threatened by everything he put his hand on. Many people believe that it was a sad day indeed when Benjamin Franklin tied that key to a kite string and flew the kite in a thunderstorm; other people believe that if it hadn't been Franklin, it would have been someone else. As, of course, it was in the case of the harnessing of steam and the invention of the gas engine. At any rate, it has come about that so-called civilized man finds himself today surrounded by the myriad mechanical devices of a technological world.

Writers of books on how to control your nerves, how to conquer fear, how to cultivate calm, how to be happy in spite of everything, are of several minds as regards the relation of man and the machine. Some of them are prone to believe that the mind and body, if properly disciplined, can get the upper hand of this mechanized existence. Others merely ignore the situation and go on to the profitable writing of more facile chapters of inspiration. Still others attribute the whole menace of the machine to sex, and so confuse the average reader that he cannot always be certain whether he has been knocked down by an automobile or is merely in love.

So here we are, a mere eighty-seven years after Thurber posed this question, facing this same question again. Was it “a sad day indeed” when Benjamin Franklin harnessed electricity, or when the fossil fuel powered engine was invented? In this essay Thurber goes on to describe three hypothetical men who start across a New York street on a red light and get in the way of an oncoming automobile. A dodges successfully; B stands still; C “hesitates, wavers, jumps backwards and forward, and finally runs head on into the car.” A man Thurber calls Dr. Bish, an early Freudian, believes C runs headfirst towards the car because the car represents…sex!

We’ve been running headlong towards that automobile, that gas powered engine now for a hundred years. If only it had been so simple, if Dr. Bish had been right and we could pull out some old Freudian theories about sex and aggression being the fossil fuel fed machine of the soul and the ego and superego being the gears needed to control that fuel. We are long past that. It’s not the fault of sex, or even of the real engines or of the fossil fuels that make them work, or the transformers or the data centers or the iPhone. We took all these machines and all the progress these machines afforded us and turned it all into money and power. And in the last thirty or forty years we fell for the tricky word neo-liberalism and allowed all that wealth to concentrate in the hands of a few greedy corporations led by equally greedy, mostly white men who can hide their money in multi-national corporations that now control and influence every (see this terrific piece in Drilled by Amy Westervelt) newstory we read, every advertisement, every consumer choice, every political choice we face.

When in the gloom of the late afternoon we finally arrive at our hotel without getting run over or seduced by a car masquerading as a lover, I am exhausted. When I tell my granddaughter that I think I’m tired because I’m such an old lady, her response is very consoling. “It’s so loud here and everything goes so fast, so don’t worry Gigi, it’s not you, I feel the same way.” Her brother agrees. Bob is equally as tuckered. None of us wants to go explore Central Park or take the tour of the secrets of Grand Central Station where for many years my paternal grandfather, who died a year before I was born, owned and operated a bar. All we want to do is find a place for dinner and go back to our room and rest.

When this Guardian interview of political theorist Ajay Singh Chaudhary about his new book titled, Exhausted of the Earth, shows up in my inbox a week later, I read it and immediately see the truth in Chaudhary’s argument that exhaustion rises from the pressure that capitalism’s insatiable demand for profit and production puts on all of life.

Are you exhausted today?” political theorist Ajay Singh Chaudhary asks over video chat on a dark Friday afternoon. This is a question he is posing not just to me, but to you, too – and it’s one he already knows the answer to. Most of us, the indicators suggest, would say we are. But Chaudhary argues this isn’t just an individual problem: “Our ecological life is exhausting, our social and economic lives are exhausting, even our individual lives are exhausting.”

We need a slower life, he argues; a circular economic system, where firms compete for the same amount of finite profit and the state dominates certain sectors. This will be good for the planet and for people, producing “a world relieved from social, economic, and ecological despair and exhaustion”.

Somewhat paradoxically, Chaudhary argues that tapping into the exhaustion is a way to unite people from all over the planet in common mobilization against capitalism’s grip. Like Diane Fisher, whose work and new book I referred to in last week’s blog, Chaudhary believes we will need mass mobilization of a whole variety of civil disobedience and that we will need to mobilize on the grassroots level of churches and labor unions.

Exhaustion as motivator. Exhaustion as unifying force. Wow. Now that’s a reframe but the truth of it does regenerate me!

The next day we scuttle a plan to go to the top of the Empire State Building when we learn they are charging hundreds of dollars for the view. Four million visitors from around the world come every year to look out and down on mankind’s glass and steel creations and marvel at himself. I guess a few hundred dollars for that view is worth it for many. But it wasn’t this view I wanted to show the children or this story of the building’s glory I want them to take away. I want them to know what it cost in human terms for this building and so many others like it to be constructed.

Many of my readers know this story I am about to tell, but some of you are new here and the story is so seminal for me that I never tire of telling it and I often learn something new when I look at it again from another angle. My maternal grandfather, their great-great grandfather, was a safety engineer employed by Travelers Insurance when the Empire State building was constructed. It was his job to keep men from falling from the sky, from being maimed by machines. Back then there was no regulatory body like OSHA to protect workers’ safety and, as the Uber driver, himself a medical technician who supports construction companies tells us as we drive past the Empire State building on a trip downtown to visit the Statue of Liberty, “back then men who worked on those buildings died like flies.”

Exhausted and likely depressed, that grandfather quit his job, retired early to a home on Long Island in a town that was then fairly rural, a town next door from where I grew up.

Now I have a new way to think about my grandfather’s response to his exhaustion from the grip of capitalism’s rise and see his turning his back on it as a courageous act of rebellion. He walked away from the status, the money, the corporate ladder. He slowed down. He set up a studio in his house and learned to paint and carve. Everything he designed was miniature: small 4” x 4” paintings of rural life and most notably, he carved tiny chairs. The chair, symbol of rest and time out and hospitality. Have a seat, give your feet a rest, sit down beside me, his chairs defy the coda of capitalism and suggest a whole other paradigm for our lives.

I wonder how my grandfather’s exhaustion/rebellion shows up here on this page right now as the motivating factor for this writing, this work that calls me to commit to figuring out a way to live a life that is not strangled and put in peril by the forces of greed and the institutions that feed that greed.

As is evidenced by this essay, we made it back alive. Just to be sure I didn’t forget how exhausting the city is, I came down with Covid two days after our return and I haven’t been out of the house or for that matter out of bed for much of the week. This morning, I am much better. I haven’t been able to ask the grandchildren what their takeaway from the city is but I would bet one of their top memories is captured in this picture!

Change is coming. This week FreeportCAN will host the second in a series of workshops led by a young man who has been studying the question Fisher and Chaudhary attempt to answer: how did we get here to this place where we and the natural systems that support us are on the brink of exhaustion? And what do we do about it in the little bit of time left before things get really really bad. Richard Gorvett is introducing us in Freeport to something called Regenerative Design and together we will examine its principles of living in harmony, not with the principles of capitalism, but with the principles of Nature, and together we will dream a way to begin to do that here, now, in this not yet totally exhausted place where we call home. So if you too are exhausted by the life unfolding around you, come join with us.

P.S.

There is one more story about our time in New York I haven’t told you. It is a story awash in all the themes of this essay, my silence the product of the fact that the maw of unfettered capitalism is one of the forces playing its nasty role in the fate of this story. Writing about it may risk feeding its voracious belly. Someday I hope to be able to write about it.

For the 25 years I was a software engineer, I refused to work on software whose application was immoral (e.g., it monetized destroying privacy or it enabled the tracking of all a person's contacts or exchanges or it made the slaughter of animals more efficient), and I had to quit a few jobs in the process when decisions up top turned neutral work into evil work. Over the course of my career I knew hundreds of engineers and I never met a single other one who cared about the implications of their work on society. In conversations, when I would mention how software "features" could be misused, when I discussed how software gives people more power and that puts the onus on the user to be ethical, but power corrupts, when I posited how our product could be misused, say, against our domestic population, inevitably my colleagues would shrug. "But it's cool," they would say. I would raise the principle that without enablers, evil people in power can't implement their nefarious schemes. "If I don't write it, someone else will," they would say, "I might as well profit from it." I never met a colleague who cared. Eventually I reached a point where I couldn't even find a job anymore where the product was morally neutral and I left the field.

"You can't stop progress," they say, without examining what they define as "progress." So much facile thinking.

I read a headline in the WSJ today that Houti terrorism in the Red Sea is hampering repair to the cables that carry international web traffic. People who aren't in technology aren't aware how vulnerable the whole system is, how the electric grid and the internet have surprisingly few points of failure, and what the ramifications of a disruption would be, given that we have become completely dependent on electricity and the internet for just about everything. When I left software, I went to the Maine woods, where we frequently lose both electricity and internet. I learned preindustrial skills. Is that going to keep me safe? I don't think so.

I actually think our biggest danger soon will be violence. The internet has enabled the worst in propaganda, it has divided the country — the world — with lies and stoked their fears. As resources get tighter, as weather gets worse, there's going to be a lot of murder and war. It will be part of how the earth rights itself, textbook Malthus. Our system, which we have so "intelligently" devised for its cool factor, our system which is so out of control, is going to be a big part of what wipes out most of humanity, brings us back to a few scattered groups of at most a few hundred souls each, just like when humans first developed. And when we are out of the way, the earth will heal.

I wish we were more intelligent, I wish more people in positions of power would make wise decisions for the good of all creatures and the land, but I am sure we are going to continue on our course as long as there is a drop of oil to sell, a people to squeeze, a resource to steal, a profit to be got. But the earth thinks in geological time, and she seeks balance. She will find it.

Brilliant essay, K! Restacking to Notes where everyone can read and learn from it.