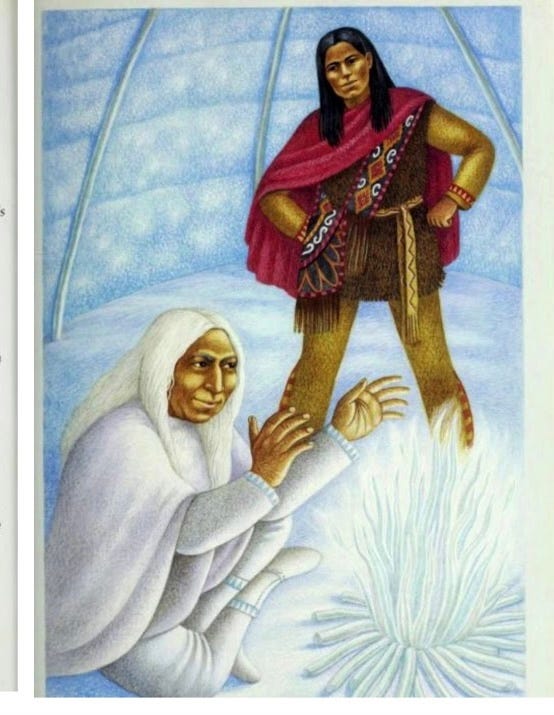

Grandmother Woodchuck and Gluscabe

The Power of the Stories We Tell—Learning from Indigenous Knowledge

This era is for visionary death doulas with time-traveling presence, able to stand in this moment full of embodied wisdom from our lived and ancestral experiences, and ripe with possibilities and practices for a future that is nourishing for all of us. adrienne marie brown

By all accounts we humans are stuck. News of the suffering of all life on this planet reaches me daily, leaving me feeling small and lost. It is at these times that I remind myself that I know something about stuck places, about how to think about them and emerge from them. For fifty years people knocked on my door, followed me into my office, sat across from me and asked me to help them find a way out of the suffering that wells up from the airlessness of stuck places. They came to me because, in a million ways that were all the same, yet different, they were unable to find a way out, a different door that led in another direction.

In time I came to see that the way out was not a behavioral health plan or a new medication. I came to see that it was stories that locked people into airless rooms and stories that opened the doors to nourishing possibilities. I saw myself not as a psychotherapist as I’d been trained, but as storyteller, dismantling old stories and weaving new ones.

Our minds are woven by story into patterns of thought and aspiration and interpretations we’ve laid down in our brains about crucial aspects of what it means to be human. Neuroscience has, in the last ten years, confirmed Freud’s proposition that childhood experiences shape the essential patterns we follow for life. The brain organizes these experiences into patterns and those patterns become stories we use to guide our lives. What can we expect from relationships? What constitutes a self? What is expected of me to gain esteem, support, care? How am I expected to think about the natural world, my place in it?

Tell me your story. Often, like a good novel, I could hardly wait for the story to be told, to discover ways for us to unravel the themes of the story and find new characters who spoke new lines and made different choices.

It is from this point of view that, when the news of another fire or the death of an orca whale reaches me, that I ask: Are we doomed by some fundamental truths about human nature or evolution—that man is destined to acquire and accumulate wealth; that high population and agriculture and industry ensure our disconnection from each other and from the land and require kings, bureaucracies, and presidents to maintain order? Or, are we simply blinded by our stories? If it is the latter, then I better get back to my old work of finding in stories new ways to be in relationship to the throbbing world around me.

The book, “The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity” by David Graeber and David Wengrow answers these questions by examining history from the point of view of archeologists and anthropologists. The authors report that new evidence from their fields reveals that throughout the long arc of time there are different, much more hopeful stories about human nature and how we can live together than the ones we Westerners have come to see as inevitable and true. We’ve got our stories wrong, they say. We’ve been blinded by our old stories.

To my delight, the authors begin their argument about new stories we need to learn from not in the far distant Paleolithic past of hunter gatherers or ancient China, but in the same place where I have been walking and wondering: in the forests of the Northeast, in the land of the Wabanaki! I have to look no further back in time than four hundred years to find a fully developed, thriving culture which met the needs of all its peoples without rapaciously destroying nature. The authors tell us that:

For European audiences, the indigenous critique would come as a shock to the system, revealing possibilities for human emancipation that once disclosed, could hardly be ignored. Indeed, the ideas expressed in that critique came to be perceived as such a menace to the fabric of European society that an entire body of theory was called into being, specifically to refute them. As we will shortly see, the whole story —our standard historical meta-narrative about the ambivalent progress of human civilization, where freedoms are lost as societies grow bigger and more complex — was invented largely for the purpose of neutralizing the threat of indigenous critique.

Holy smoke.

The stories of the spirits that walk in my woods were so dangerous to the minds of the early settlers here, right here on land I inhabit, that they or their kinsmen or mine destroyed their stories, obliterated their contributions, their insights, their highly developed systems of trade, care, governance, ecology. This finding feels as momentous to me as the finding I wrote about earlier regarding the Portland minister who offered a bounty on the scalps of Native American men, women and children. It twists the story of the genocide of the Native Americans to encompass not only our (our as in I am living on that land and living the European story of success in every way) rapacious wish for land and wealth, but also our wish to be seen as superior and our inability to face the failures and limits of our own stories, of the entire way in which we have constructed a self.

It was the Jesuits who first sent word back to the continent about the Mi’kmaq he encountered in 1620 in Nova Scotia.

Father Pierre Biard wrote:

For, they (the Native Americans) say, “you are always fighting and quarreling among yourselves; we live peaceably. You are envious and are all the time slandering each other; you are thieves and deceivers; you are covetous, and are neither generous or kind; as for us we have a morsel of bread and we share it with our neighbor.”

Biard was most incensed because the Mi’kmaq asserted that they were “richer” than the Europeans in so far as they had ease, comfort and time. And, as we know from last week’s blog, the forests and the rivers and the land itself were far richer for their presence than ours.

All this brings me back to the beginning. Now I am the person who needs to sit across from the Wabanaki sachem and ask her to help me find new stories, so that I might find a way out of my suffering, my airless room.

“Tell me your story,” I say to the woman we met last week on the banks of the Androscoggin River. Tell me a story to help me design a new story, “ripe with possibilities and practices for a future that is nourishing for all of us.”

“I will tell you the story of Gluscabe, my people’s mythological god-man and his grandmother, Noogame,” she replies. “As you are an old woman like Noogame this is an important story for you to know as you reflect on your grandmother role in the cosmos of time. And since this is a story about taking more than is needed by deceitful means, it is a story you should tell your children and your grandchildren.

One day Gluscabe, said Grandmother Woodchuck, was in need of a game bag, so he asked Grandmother Woodchuck to make him one. She pulled all the hair from her belly in order to make him a fine bag. To this day you will see that all woodchucks still have no hair there. Now this game bag was magical. No matter how much you put into it, there would still be room for more. And Gluscabe took this game bag and smiled. “Grandmother," he said. "I thank you."

Now Gluscabe went back into the woods and walked until he came to a large clearing. Then he called out as loudly as he could, "All you animals, listen to me. A terrible thing is going to happen. The sun is going to go out. The world is going to end and everything is going to be destroyed."

When the animals heard that, they became frightened. They came to the clearing where Gluscabe stood with his magic game bag. "Gluscabe," they said, "What can we do? The world is going to be destroyed. How can we survive?" Gluscabe smiled. "My friends," he said, "just climb into my game bag. Then you will be safe in there when the world is destroyed."

So all of the animals went into his game bag. The rabbits and the squirrels went in, and the game bag stretched to hold them. The raccoons and the foxes went in, and the game bag stretched larger still. The deer went in and the caribou went in. The bears went in and the moose went in, and the game bag stretched to hold them all. Soon all the animals in the world were in Gluscabe's game bag. Then Gluscabe tied the top of the game bag, laughed, slung it over his shoulder and went home.

"Grandmother," he said, "now we no longer have to go out and walk around looking for food. Whenever we want anything to eat we can just reach into my game bag." Grandmother Woodchuck opened Gluscabe's game bag and looked inside. There were all of the animals in the world.

"Oh, Gluscabe," she said, "why must you always do things this way? You cannot keep all of the game animals in a bag. They will sicken and die. There will be none left for our children and our children's children. It is also right that it should be difficult to hunt them. Then you will grow stronger trying to find them. And the animals will also grow stronger and wiser trying to avoid being caught. Then things will be in the right balance."

"Grandmother," said Gluscabe, "That is so." So he picked up his game bag and went back to the clearing. He opened it up. "All you animals," he called, "you can come out now. Everything is all right. The world was destroyed, but I put it back together again."

Then all of the animals came out of the magic game bag. They went back into the woods, and they are still there today because Gluscabe heard what his Grandmother Woodchuck had to say. (Caduto) .

I invite all the Grandmothers reading this essay to join me as I take up the invitation from Grandmother Woodchuck to don a coat of woodchuck furs and try out the voice of Grandmother Woodchuck. We are the Grandmother Woodchucks and we have much to teach about the harm caused by the old stories we learned as kids about how much we could stuff in our magic bags!

Thank you for sharing this story, Ilo. How fortunate you were to have these stories embedded in you by your Pawnee stepfather. I just read your beautiful ode to your spiritual teacher, Master Ku San. I imagine those Pawnee stories left you open to the teachings of Ku San. "The thousands of worlds/which are like grains of sand/ become one whole/White snow fills the courtyard/ and magnolia blossoms bloom." Thank you thank you.

Another wonderful installment and a voice calling in the wilderness. I had the great good fortune to spend part of my youth in an indigenous household. My stepfather, Garland, was a Pawnee and had been raised himself by his non-English speaking Pawnee grandparents because his Pawnee parents had died from disease. Fluent in the Pawnee language himself, he was of the last generation of such speakers and had a wealth of stories similar to what you have shared with us. Thank you!