The shopping carts that flew out of the cavernous opening of Costo’s front door last Sunday were twice the size of any shopping cart I’d ever seen. The eyes of the shoppers hunched over those behemoth carts twinkled with satisfaction, their faces shone, like the face of a hunters who’d just bagged a deer, I mused. In the carts were giant boxes of cereal and detergent that looked destined for a civilization of giants. In one cart a 4’ artificial Christmas tree sat beside a large round violet and black decorative pillow embroidered with an image of an inhuman face with bulging eyes and a gaping red mouth.

I need, I thought to myself, to take a picture of this, this antithesis of attunement to Mother Earth, the internal process I’d vowed just the day before to pay attention to. But before I could gather myself enough to stop gaping and take out my iPhone, a Costco Security guard politely but firmly ordered my friend K. and me off the property. Costo’s Grand Opening was the day before and fourteen of us were there as part of a National Third Act action to encourage Costco to drop their Citibank credit card and ask shoppers not to apply for that Costo card as part of their membership.

This kind of activism is new to me and, unlike my friend who has been an activist her whole life, I felt very shy as I handed out flyers about Citibank’s ongoing billion-dollar investments in new fossil fuel infrastructure.

I was, honestly, relieved to retreat to public property on the access road to the sprawling Costo store and, in anonymity, hold up our banners. At one point, a different security guard, this one looking very angry, walked across the street and took pictures of us holding our signs. I did, by then, have the courage to ask him if he knew why we were here and if we could give him a flyer. “I know why you are here”, he said, his eyes scrunched up and his mouth looking dangerous like he could bite us, “you are here to hurt us. The people of Maine said they wanted Costco to come here. Now you are ruining that.”

Oh, the question of harm. Of greater harm. Of whom and what is harmed. It is a difficult question to answer in this culture where we are bred to be disconnected from the harm all that stuff is causing Mother Earth.

Costco is the third largest retail corporation in America and this man, newly employed by this corporation on whom he is now financially dependent, feels empathy for the corporation. God bless him. He is a true American, forged in his disconnection from nature by four hundred years of colonial Western thinking that birthed this Costco, here on land that was once a thriving woodland and is now paved over with asphalt and crowded with cars fighting for a place to park.

“I drink the cold air in the low blue gleam that sparkles in the snow. Every inlet and outcrop of this place I love. We are taught early here to see Nature as a foe to be subdued. You could say that this island and her bounties became the first of my false gods, the original sin that begot so much idolatry.” Geraldine Brooks, Caleb’s Crossing.

The fictional character who speaks these words in Brooks’ novel is the granddaughter of the first settlers of Martha’s Vineyard and is raised to believe that her attachment to nature is a sin, an idolatry to a false god. In some ways, that’s the message of the security guard last Sunday morning: we were worshiping false gods and in so doing are creating harm to his god: the corporation.

I didn’t actually cause any trees to die in my backyard this week, and no one I know drowned or starved from the consequences of a warming world. But a piece I read in the Guardian made very real my duplicity in the harm my lifestyle wreaks upon this earth. And news arrived in the Washington Post that the world had for the first time reached a global average temperature of 2 degrees Celsius, that line in the sand that portends “calamitous consequences.”

Contemplating all this harm, I redouble my efforts to attune myself to Mother Earth. I pull the book Restoring the Kinship Worldview off my bookshelf and discover Darcia Narvaez, PhD, a psychologist at Notre Dame, who writes extensively on both the need for attunement to nature if we are to survive as a species and on the kinds of experiences which would encourage that attunement. Her website is filled with these attunement ideas, as well as links to papers in ecopsychogy and philosophy and economics.

One of the things she does with students is called the 28 Day Eco Attachment Dance. For each of those days, Dr. Narvaez gives an exercise, like this one from day 2: “Think of a favorite plant and feel gratitude for its life and its gifts to you.”

Try to imagine yourself with that plant brightening your mind’s eye. Perhaps it’s a daisy. For me it would be the sea of moss riding the earth outside my window. Now check your reaction to this suggestion. Do you feel a little squirrely wave of discomfort, a little part of you saying to yourself, this is foolish or childish or weird or way out there like those radical tree huggers? I confess I have all those feelings! I confess I didn’t trust myself to take this exercise seriously.

I needed help.

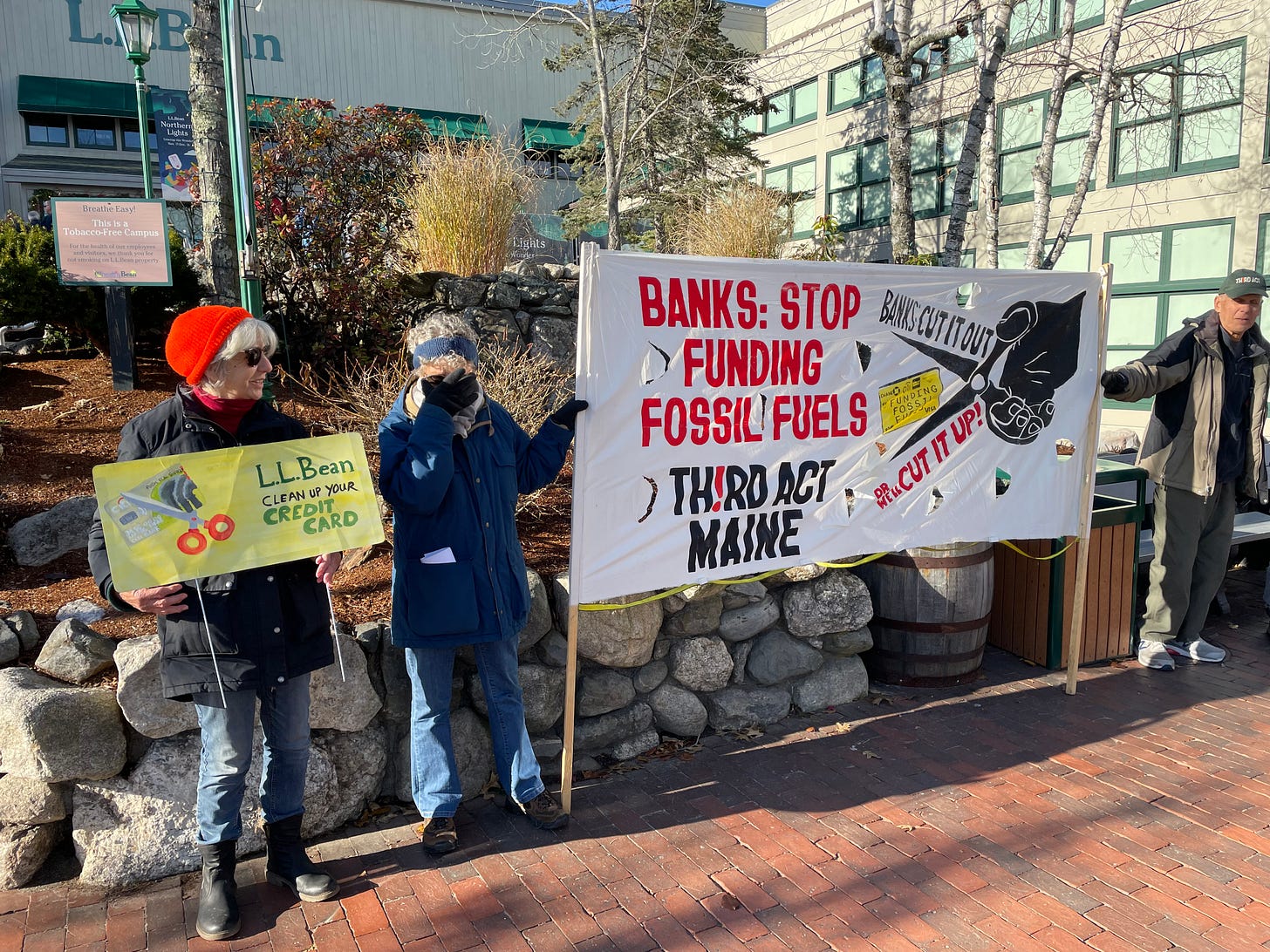

So, I designed an experiment! I invited five of my Third Act friends to come back to my house after the demonstration on Friday, Black Friday, in front of the LLBean store designed to get Beans to drop their Citibank card. I lured them with the promise of newly made turkey soup, a slice of clementine cake and, lastly, a chance to hug a tree. I was afraid they might think I’d lost my mind, so I couched my invite in my clinical curiosity about whether this exercise would change their experience of themselves and the tree in any way.

Not one of my Third Act buddies thought I was being silly or foolish. They followed me home and as we drank a cup of tea to warm up, we reflected on the experience we’d just had at Beans. The old hands at this kind of demonstration were resolved to the idea that success couldn’t be measured in anything that happens in any one day or even year. But I was truly ungrounded. I’ve never felt so invisible—not one person who passed me on the sidewalk in the whole time I stood there looked at me or my sign. A smattering of people made fun of us. Some people were angry and yelled at us. There was but one ally among all those shoppers.

Beans is another corporate god, and, again, our presence offended the god of those shoppers. On Black Friday no less! No one wanted to feel discomfort on this holy day of consuming.

The tea finished; it was time to go outside. In preparation, I put the exercise in the context of what I remembered about attunement with infants. Early researchers stressed how important it is for the caregiver to come into harmony with the child’s rhythms. If the child is quick to respond to a smile, but the mother is slow, mutual attunement happens when the mother speeds up and the child slows down. The same is true with hugging or with patterns of speech.

“Find the tree whose rhythms call to you”, I told my friends. “Observe how your body feels, what comes to your mind, what associations you make, then come back in and we will discover what that was like for each of us.”

What I realize as I write this is that the surprise of this exercise is not simply what I learned and felt about attunement to trees and all the dirt and duff that support trees, it is also about how my relationship to my five friends was deepened and informed in a way that makes me see them more clearly and care about them more keenly.

It is no surprise that what each person experienced and described represents a little beech nut of themselves, of their experiences with forests or with certain white birch not gray birch or with the sky. Because each beech nut took in their tree in a different way, each of their experiences expanded my own vision. All but one person felt the energy of the tree enter them and were calmed and centered by the experience. No one felt that the tree attuning to them but that didn’t matter. One confessed that if he had asked his family to do this at their Thanksgiving get-together, they would have laughed at him, so he, much like me, was glad to be with people who would not laugh at him. For everyone, I think the experience was something like play, something like spirituality, something tinged with childlike curiosity and wonder.

Someday I will write up my experience with my tree: an old gray birch, entwined in the body of another gray birch, both bodies layered with moss and brown lichen and studded with white specks of something that has no name I know of. I plan to learn its name.

But I want to close with a warning. The more I pay attention to this natural world and attune to where and what kind of life gave me the bounty I live with, the harder it is for me walk uptown amidst all those shoppers rushing into our stores and not feel deep sadness and even anger. “STOP, think about this”, I want to yell, “Come with me to the forest. Come hug a tree, whisper to moss, breathe the pine into your lungs, then decide what the real cost is of all this shopping.”

They’d come lock me up, don’t you think?

Next time you have a few friends over, I urge you to try this experiment. Blame it on me. Or try it with a child or grandchild. On Thanksgiving I asked my 13 year old grandson, Finn, to come stand on the back porch with me and listen to the sounds in the forest. He heard woodpeckers tapping and bluejays singing and the sound of the wind in the trees. He held my hand as we listened. Later, when the family was half way through our mashed potatoes and turkey, Finn and I each read a line of a Billy Collins poem. Like my experience with my Third Act friends, attuning to nature with Finn deepened not only our attachment to the wild things of this forest, but to each other.

As If To Demonstrate an Eclipse

I pick an orange from a wicker basket and place it on the table to represent the sun. Then down at the other end a blue and white marble becomes the earth and nearby I lay the little moon of an aspirin. I get a glass from a cabinet, open a bottle of wine, then I sit in a ladder-back chair, a benevolent god presiding over a miniature creation myth, and I begin to sing a homemade canticle of thanks for this perfect little arrangement, for not making the earth too hot or cold not making it spin too fast or slow so that the grove of orange trees and the owl become possible, not to mention the rolling wave, the play of clouds, geese in flight, and the Z of lightning on a dark lake. Then I fill my glass again and give thanks for the trout, the oak, and the yellow feather, singing the room full of shadows, as sun and earth and moon circle one another in their impeccable orbits and I get more and more cockeyed with gratitude.

Thank you so much for this witness, friend! It is uncomfortable to get out there and bear witness, but the right kind of discomfort I think

Is this your poem, Kathleen? So wonderful thanks for your code red.