Living in An Old World Movie Set

Envisioning a New One, January 7, 2024

It’s all happening too slowly for her. She doesn’t have much time left. The number 79 is cut from red and blue pieces of cardboard on the birthday card her son gave her a few nights ago at her quiet birthday dinner. She doesn’t want to die in this place where everything feels like it’s from a time before, a time when no one thought about the real costs of superhighways and prime rib and fast fashion and the oil furnace chugging in the basement.

On New Year’s Day she read an article published by the world’s oldest national scientific academy, The Royal Society, established in 1660, home to the groundbreaking work of Charles Darwin and Isaac Newton and Albert Einstein, which made her even more impatient with the slow pace of change she sees around her. Never before has its journal, The Philosophical Transaction of the Royal Society, put out such a dire warning:

On the one hand, this ecological dominance of humans could be seen as the ultimate evolutionary success of a species. On the other hand, the overlapping systemic and global risks that mark the Anthropocene hardly seem like a success. Human activities are threatening the stability of the Earth's climate, the survival of many co-inhabitants, and indeed the basis for the stability of human civilization [21,25–27]. Dealing with these global sustainability challenges is the central question for whether human success will be long-lasting or short-lived, and whether it will be inclusive or for the few [24].

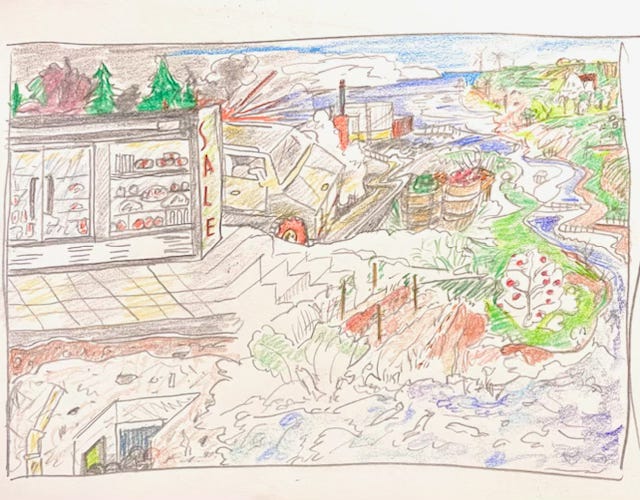

As she goes about her days and sees little change happening, she feels as if she’s living in an old movie set in what has come to feel like the Old World. A drive uptown, a visit to the local grocery store, a trip to the library: it could be 1975 for all the real change that’s visible to her. She feels dazed and off-center, like she’s dangling between real and unreal, between past and future, between safe and unsafe.

In her mind she sees how it could all be different. She sees how we could be living without causing unnecessary harm and pain and death, how we could be more aware of our relationships to what we use and eat and wear and how we move and heat and how we give thanks and what we take responsibility for and what we cherish and how we care for each other.

She knows the New World she envisions is not science fiction or wishful thinking or something that no other group has ever done before. She agrees with the data scientist Hanna Ritchie, author of the new book, It’s Not the End of the World, that we have all the tools in hand to build a sustainable planet, now.

In the New World of her imagination, each New Year begins with a ceremony of gratitude. She rises and puts on boots and a warm jacket and drives the few miles to the parking lot by the wooden bridge that crosses the Little River. Facing east in this place once called Dawnland, the sun rises from the waters of Casco Bay, offering her gift of light. There she meets friends who will join her in a ceremony she read about in Robin Wall Kimmerer’s book, Braiding Sweetgrass. Together, holding gloved hands in a circle, they read the ancient words of the Haudenosaunee Thanksgiving Address.

She and her friends will begin their year grounded in deep respect not for a shiny trinket or a moment of fame, but for Mother Earth, the plants, the fish, the water, the moon, the trees, the sun, the animals. Humbled and grateful and connected not just to friends but to all of life, she returns home with a mind prepared for the systemic leaps we need to make to swerve civilization towards a life-enhancing culture.

Later, she’ll go uptown. But she won’t take her car because in the New World the streets in Freeport have been engineered for safe walking and biking and a culture of biking has grown so strong that cars slow down and respect the bikers. She isn’t afraid to get out her electric bike and don her extra insulating gloves and boots and pants and pedal uptown!

On the way there she passes two co-operative solar farms, the shiny black faces of the solar panels facing the sun, absorbing its energy, thumbing their proverbial noses at fossil fuels. In the New World, CMP has been replaced by community owned utilities and the grid has been updated and everyone in town is happily heated and powered by low-cost renewable energy.

When she opens the door to the local grocery to pick up some fish for dinner, she won’t be greeted by a 20 foot refrigerated glass shrine to meat in the center of the store, instead there’s a whole array of locally grown grains and beans and vegetables and fruits and even some locally grown chickens. And off to the side, the shrine to farmed fish and shrimp will be stocked with oysters grown in our waters and clams and wild caught fish. And oh! the packaging! A whole revolution in packaging, all of it smaller and all of it compostable and all of it easy to open.

Perhaps on this ordinary day in the New World she will also stop by the school to mentor students on the ways they can contribute to an ecologically balanced community. Instead of the silence and avoidance which currently characterizes the way the threat of climate change is handled in the schools, she finds there an openness to grappling in positive ways with the threat children know all too well hangs over their future.

Just before going home on this cold day, she thinks about a pink sweater, a new pink sweater to wear to the concert at Meetinghouse Arts. New. New to her that is. There are so many resale shops uptown now she will surely find what she is looking for. She might even consider stopping in at L.L.Bean, a corporation that responded to the concerns of many of its customers and came to recognize the harm caused by their old marketing scheme to mesmerize shoppers into buying more and more useless stuff by the flashy idea that one click of their dirty Citi Bank credit card will turn them into a romanticized idea of a true Outsider, a sort of modern Thoreau.

In this New World, Main Street is no longer a death trap, all the cars are gone, and trees shade the street and dance in the wind. All the boring outlet stores are gone too, replaced by affordable housing units or local businesses. She parks her bike and locks it up on a handy bike rack and goes inside her favorite resale shop where she is greeted like an old friend. A pink cashmere sweater from the 70’s is waiting for her on one of the racks. “It looks beautiful on you,” the shop owner declares. Beautiful in her 80th year.

In this New World, old people are beautiful and old people aren’t so numbed by ageism that they are afraid to take on the role of Elder, guiding the younger generations out of the Old World and into the New, protesting in the streets against the banks that dare to fund death-spewing fossil fuels. She believes that the “stability of human civilization” rests in part on new stories, new narratives and as she pedals home, she resolves to continue telling stories, to take on her role as Elder and, together with other Elders doing this New World work, radiate the beauty that is in all of us and all around us.

A lovely vision, Kathleen, from a lovely writer. Mike Shanahan in his excellent Substack wrote recently about an idea that fits in with your love of the native peoples and their wisdom. It's about biodiversity and legally protected Sacred Forests. Where are our Sacred Forests in this country? Mike cited an article in a respected science journal that looks at contemporary such forests:

https://doi.org/10.1111/csp2.13055

Wonderful story- you replaced an old story with a new one, just as you encouraged us all to do in your last post! Thanks for the beautiful example and inspiration. Happy birthday, oh wise elder! 🎉