Love in the Time of the Pandemic

Freeport, February 14, 2021

“Good apples, don’t you think?” said the handsome, dark-haired man whom I’d noticed earlier (with a little flicker of fancy) sitting a few seats to my left during class. From across the long table laid out with chips and cups of beer, refreshments for the lot of us who’d signed up for the sailboat racing course, he caught my eye and nodded at the big bowl of gleaming red apples before us. “Mmm,” I murmured, reaching for the biggest, reddest one, taking a bite. Laughing, lightheaded, suddenly under a spell.

A few days later, I called my mother and told her I’d met the man I was going to marry. “Oh! What’s his name?” she asked. “Bob,” I said. “What’s his last name?” “Umm, I can’t remember.” My poor mother. Six months later, we were married under a tent on a polo field outside of Chicago. A stormy day for starters, the sun came out just as the guests arrived. My uncle sang Danny Boy. I danced with my father. Friends, many of whom have already died, toasted us and wished us a long life together. I floated. I flew. I was in love.

Falling in love hijacks the brain, researchers like Helen Fisher tell us. Forty-seven years after that phone call to my mother, I get why we are wired that way. If I’d had any idea of the risks and complexities involved in that snap decision to marry, I’d still be single, dithering about all the possibilities and unknowns. The dopamine kick from the pleasure centers of the brain throws fairy dust over our judgement centers. It lasts eighteen months. Just long enough, from the point of view of evolution, to ensure the birth and survival of a child!

Neuroimaging reveals that novelty and surprise are able to revive some of the early passion of a relationship. The only surprises this year have been ones that make us anxious about well, everything: dying, breathing, losing your job, losing our democracy, getting food, unmasked strangers beside us in the grocery store. We aren’t programmed to think about sex when a bear is chasing us in the woods and there have been bears galore for almost a year now.

Your sweetie in the same plaid flannel pants, the same gray t- shirt, straggly hair months overdue for a cut, mismatched socks, may be a comfort for the heart some mornings, but not, after months in the same apartment, scrubbing the kitchen together for the umpteenth time — a big hit for the libido. Being together with a partner 24/7 in the same space, with very little change from day to day, week to week, perhaps with children stuck at home too, is not what the sex therapists would recommend to keep the ardor of desire burning.

So here we are, almost a year into a world pandemic, in the same rooms we were in last year, our usual diversions: restaurants, movie theaters, travel, shopping, entertaining: shut down. We’ve been staring at the same partner now for a long time. Or we’ve been living alone for what feels like forever. I’ve been a couples’ therapist for longer than anyone I know, and I have been seeing a good number of couples through this time. The rumor you’ve heard about how all the couples’ therapists (of whom there are few and even fewer with good training) are busy is true. It’s been a hard time for many couples.

A Portland divorce attorney I know, was quoted in the Press Herald as saying that he and all the other divorce attorneys in Maine are slammed with cases. Marriages that were holding on by threads were too unstable to make it through the increased intimacy of covid quarantine. Starting precipitously last March, all kinds of previously agreed upon patterns had to be renegotiated: personal workspace, clutter, childcare and discipline, divisions of labor—all while scared and uncertain about everything beyond the front door. The subtle (and impossible) expectation in our culture that marriages should fulfill all the needs of an individual was suddenly made even more manifest as outside diversions fell away. Couples living in stepfamilies, with kids at home, had a particularly difficult time of it from my experience.

But I want to tell you some positive things I’ve observed about love in the time of the pandemic. I have the sense that relationships are moving from the shadows, from the background where their importance was shaded and obscured and minimized by all the other neon lights flashing around them: work and fitness workouts and getting the car fixed—to the foreground where they’ve become larger, more central to our vision and our experience, more woven into our imagination, more enticing, more longed for.

I am not only talking about couples and romantic relationships, I am talking about friendships and family. Suddenly we need each other more than before and there’s less to distract us from our need. Suddenly, the ache of feeling cut off from grandchildren or parents or friends make us take these relationships less for granted.

And of course, there’s death. If, with the squirm of a sticky covid virus in our lungs, one of us could get sick and die, well then, it’s time to pay rapt attention to the person sitting on the other side of the table. Time, perhaps, to dance in the kitchen again. Or time to check on siblings, friends. Time to make amends. Time to be grateful, to forgive.

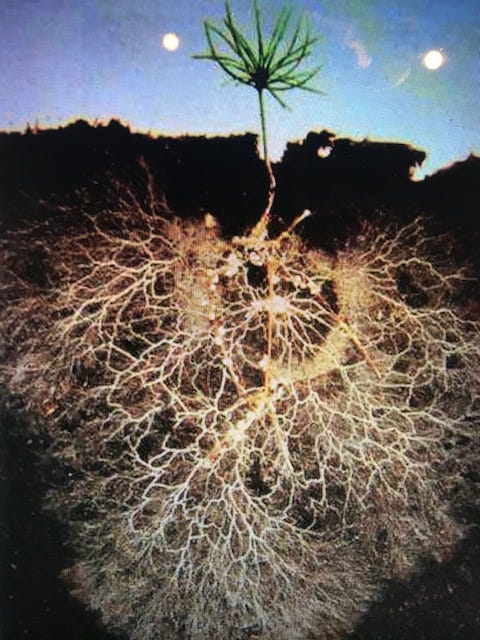

Have you heard about the trees? How they are not what they appear to be. They are not separate beings, independent of each other, waving to each other only when the wind blows, grabbing their own share of rain and carbon and sun whenever they get the chance. Only recently have scientists learned the truth about trees. Underground, previously invisible and unknown to us, trees are involved in a complex network of connectivity. Fungi: quiet, ordinary in their own way, join together with the trees in a network (called a mycorrhizal network) and together they care for each other. The trees provide sugar for the fungi and the fungi in turn offer a steady supply of carbon to the trees. The health and survival of the whole forest, even the largest of trees, depends on this silent, invisible, almost humble, process of mutuality and care.

I like to think that maybe this is what has been revealed to us about ourselves in the time of the pandemic. That in order to survive we need to care for each other by exchanging the basic, simple nutrients of love: kindness, compassion, gratitude, affection, attention. Some of us are just learning how to give these. Some of us are learning how to receive what is offered. Some of us have not yet found a warm spot in a mycorrhizal network. But I feel many of us working harder at connection. Reaching up towards the sun and down deep into the soil for succor. Here in the time of Covid, every day is Valentine’s Day and everyone in our network is our Valentine.

In a few minutes Bob, whose last name I eventually did learn, will come out of the darkness of our bedroom and say good morning, how are you, how did you sleep. He will get his tea and we will sit together in front of the big windows that look out on the forest and talk about the small things that weave us together. I will tell him how much I cherish him as one of the big trees in my forest who has sustained me, protected me, held me, shielded me, for forty-seven years. Old love is soft, old love is grateful, and old love is aware there isn’t much time left.

Happy Valentine’s Day, Dear Readers!!