And now, reader, let us return to the banks of the Androscoggin River where we left off last week when I posed the question of who or what we have to blame for the climate crisis and the cascade of ecological collapse we now face? Is it the fault of technology and, if it is, should we then look to technological inventions to save ourselves? Or is it something more basic yet: is it the result of the stories we construct about ourselves as humans in relationship to each other and to the ecological world?

(To find past essays, click on the title above and it will take you to the website. Scroll to the bottom of each piece and you will find all the essays sleeping there quietly.)

For a brilliant essay which addresses the technology side of this question, I recommend this week’s Substack post by Jason Anthony entitled Aliens on Our Own Planet about the way in which mega corporations have colonized our existence and decimated our ecosystems.

Arguing, as I am, that we must examine the basic assumptions about how we construct ourselves in the world in order to make the kind of changes we need to make, I believe it is important to summon the stories of the Wabanaki I encountered so suddenly in my woods last summer.

In the last post, I promised to return with the story of the encounter between the English settlers and the Wabanaki in 1673 so that we could decide together from the point of view of our current crisis, which of these two groups deserve to be seen and admired?

Let me begin.

It is 1673. We are standing on the banks of the Androscoggin River, just above the Pejepscot Falls in a place that is now called Brunswick. It is April and the snow is melting fast in the mountains. The river is running fast and cold. British settlers who in two years would fight the Native Americans in one of the bloodiest wars in history, have just set up a commercial fishing operation below the falls, likely a series of branches woven together into nets called weirs. The salmon are migrating upstream in such great numbers that they “could almost walk on their backs.”

From the other side of the river, the Wabanaki are watching. They have just recently paddled their birchbark canoes downstream from their inland winter home carrying with them the few belongings they will need to set up their summer camps. To say the Wabanaki travelled light is a great understatement! They owned very little and were prone to give away even the little they had if they thought someone else in their village was in need. The sight of Englishmen is not a new sight as for the last fifty years their numbers have increased as they set up villages from Kittery to Bath. But it is a disturbing sight.

At some point, one of the Wabanaki paddles across the river to speak to these white men who “take 40 barrels of salmon and more than 90 kegs of sturgeon in three weeks' time.” The Wabanaki sachem, a strong woman, sure of herself, warns the men that taking so many fish from the river in so short a time could cause an imbalance in the fish population. To the Wabanaki this behavior is akin to hoarding. They don’t tell the white men that directly, for they are too polite, but they imply it in their attitudes.

The white settlers see the Wabanaki’s complaints and the Wabanaki themselves from an entirely different point of view. In a petition to Massachusetts for help this language is used:

“The Wabanaki look upon us as unjust usurpers and intruders upon their rights and privileges, and spoilers of their idle way of living. They claim not only the wild beasts of the forest, and fowls of the air, but also fishes of sea and rivers, and so with an ill eye looks upon our Salmon fishery, and no doubt would disturb our fishers were it not under the Immediate protection of the fort.”

Soon the Wabanaki would be proven right. By the early 1800’s, mill damns in Brunswick, Topsham and Lisbon Falls had destroyed the Androscoggin River’s fish runs. By 1816 the last Atlantic salmon was seen at Great Falls in Lewiston.

And now the question: Which of these two groups from the perspective of the climate crisis deserve our praise and admiration? The Wabanaki, of course, you say. How nasty and shortsighted of those colonists to view the Wabanakis who had tended that land for thousands of years and not destroyed the salmon run or the cod or the shellfish or the forests as lazy and unwilling to share? Look where their rapaciousness and righteousness has gotten US!!

But I am afraid this argument I have constructed has led us to a dangerous place, one that, unless we are careful, will plunge us over the edge of the falls and leave us in pieces. For aren’t I, and most of you reading this, related to these fishermen? Have we not we done our fair share of overfishing and depleting the resources? Don’t all of us have the equivalent of 40 barrels of salmon and 90 kegs of sturgeon stashed in our closets? And don’t we secretly feel entitled to those barrels, entitled by our education and our hard work and years of playing by the rules of progress?

So here we are, the modern-day descendant of the fishermen on the banks of Androscoggin. Caught. Red-handed. (Red-handed is not a slur on Native Americans but an expression derived from 15th century Scotland that meant caught with blood on your hands.) We are, at a turning point. And there isn’t much time left before the river rises and the place where I am standing is bare and barren of life.

How will we go forth in life without a Gucci bag on our arm? Who are we anyway? Is it “human nature” to want to accumulate all this stuff, to have more and more of it to show how fine we are?

How do we take in the mind-altering idea that all our consumption and belief in material progress and our god given right to it is causing the terrible harm to the planet we see all around us? As Antonio Guterres, UN Secretary General told the COP27 climate crisis summit in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt said: “we are on a highway to climate hell with our foot still on the accelerator”?

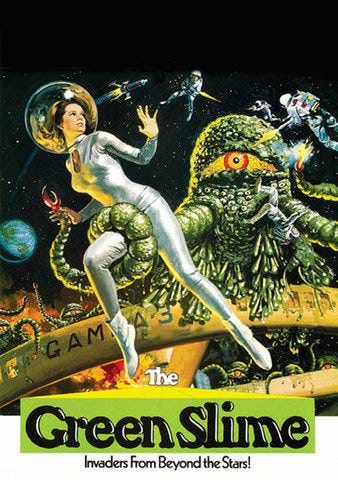

If we do take all this in, does our self shatter into pieces? Does shame, that green slimy creature hidden in the basement, crawl up the steps and throw itself over our bodies and slither into our minds? Too much shame and I am ready to run for the Amazon! Is our collective foot still on the accelerator because facing the great harm our identity-based superiority is causing makes us feel too terrible, too lost, too turned around?

It is a herculean task which confronts us. What do I need to be able to overcome my shame and anger and confusion about what’s happening now and invite the Wabanaki sachem to sit beside me on these banks and teach me what she knows about living on this land? To recognize that her people have wisdom I and my neighbors all desperately need?

I sit with this question on this dark morning before the sun has risen and I hear a voice, and a word and the word is empathy. As I sit with that word it rises and I imagine a circle filled with that empathy, warm and accepting like the edge of a lake in summer, akin to compassion or even Adam Smith’s sympathy. There is no finger pointing and no blaming. Instead there is care and curiosity.

I imagine the voice quietly telling me that it is important to understand how the stories of my ancestors shaped me to this life, how the stories they invented about being chosen by god to inhabit this land separated me from nature, glorified my independence, made wealth and property the signs of my manifest destiny; made it difficult for me to think in ways that put basic truths like the interconnection of all life in the foreground. I reassure myself that I can wake from these stories.

Be gentle with yourself and your neighbor as you study these stories, I tell myself. Then be curious about the other stories being offered by the Wabanaki and too, by historians like David Graeber and David Wengrow who are reexamining all of history and finding surprising evidence that the arc of history does not always bend towards “everything bad in human life: patriarchy, standing armies, mass executions, and annoying bureaucrats.” Be curious, listen and be changed.

On Friday night, Freeport hosted its annual Sparkle Parade, put on by the Freeport Merchants Association. Bob and I carried FreeportCAN’s banner. FreeportCAN members held signs to encourage people to have a Light Holiday! For half a mile the sidewalks of the streets of Freeport were packed eight to ten people deep. Rows of little children sat on the curb and waved. There was a lot of excitement and cheering as floats from different stores in town went by, as the middle school band played, as the unicycle troop pedaled their cycles lit with flashing lights down Maine Street. But when our group passed by there was an obvious hush. Our daughter who was among the crowd heard the people around her talk about us with complete consternation. “Who are they? What are they doing? That’s weird.”

I was aware during the whole twenty minutes that our walk from the library to Town Hall took that what we were doing made no sense to many people. That our message was as foreign to them as the Wabanaki message to the fishermen. We were offering a way of celebrating Christmas that was counter-culture and in some ways revolutionary.

If someone were to have asked me why I was holding that banner and marching, what could I say that makes sense? That buying all this stuff is killing the planet? Or should I being with story. Should I say I’ve come to see that our origin story that mankind should go forth and subdue the earth and have dominion over every living thing is just a story and that it is having terrible consequences for the earth. Should I tell them that I have discovered another origin story which the people who once lived right here in this place told to make sense of their lives. It is the story of Gluscabe. When the Creator finished making the Earth, he brushed the dust off of his hands, and from that dust Gluscabe shaped himself. Should I say that that story gives us an entirely different way to think about this moment, this parade, these gifts, our next trip to Target?

Next week: the story of Gluscabe.

Thanks for sharing. As always, I enjoy your perspective. I also felt ambiguous walking along Main Street in the Sparkle Parade with our signs declaring that we should do the exact opposite of what the parade organizers (aka Freeport Merchants Association) want us to do as we kick off this "season": shop! On the one hand, we were perhaps seen as curmudgeonly as Ebenezer Scrooge. On the other, we are doing our part, like so many millions are doing across the globe, to declare Enough with Consumerism already! Hopefully at least a few in the thousands got it!

Another fine essay, Kathleen! Thank you, and thank you for carrying the FreeportCAN banner on that cold night. Time to celebrate this holiday with the simplicity of a crèche, a baby born with very little, with helping our new Mainers and others who are housing-insecure find dependable/affordable housing.