On (L)anguishing

May 9, 2021

I’ve missed you, readers. Missed the weekly exercise of opening my computer, putting my fingers on the keys and making sense of this shattered, beautiful world in words. Missed knowing you were out there listening. Naming and witnessing is at the heart of the work I do as a therapist. Naming and being witnessed is what happens for me here in this blog. I don’t expect I will write every Sunday, and I won’t be writing a Covid Diary. Instead, I think I will call my Sunday blog “Process Notes from the End of the Road.” I hope you will join me there some Sunday mornings, your coffee in hand, the sun rising for us one more day.

**************

This story will end with a man on a bicycle who lifts the befogged swoon I’ve been in since mid-March, the one-year anniversary of Covid’s swift crash into our lives and the date I became fully vaccinated.

But first—the befogged days. In early Spring, when my last vaccine was fully proofed I felt lightheartedly optimistic. Joe Biden was calmly sitting in the White House bravely addressing the crises we still face as a country and as a planet. With the miracle of the vaccines, I and millions of others weren’t going to die of Covid. I imagined happily returning to the quiet joys of my late-stage life here at the end of the road in the forest— watching the black and white warblers return to the feeders, the hay scented ferns behind the house unfurl into the sun, the red maples punch the air with their new-green fists. I imagined finding hope and energy for my Covid-interrupted writing on the climate crisis. I imagined, too, a good frolic. But none of that happened. Instead, I have been walking about in a restless fog.

The papers are filled with stories about how our Covid year will likely change us: we will we be nicer to each other; it will be like the roaring twenties and we will want to party; we will want to keep making biscuits. A recent popular piece in the New York Times describes the mood of many in this late Covid stage with the word ‘languishing.’ Languish: to fade or to wither. This word makes me think of a hot, humid afternoon spent lying about on a on a chaise lounge beside a swimming pool, a book half opened in my lap. The word is much too unperturbed, too composed, for what this Covid year carved into the circuits of my brain. Languish, I drop the L—anguish. I feel anguish. And fear.

Like Alice in Wonderland, when the pandemic arrived, I, and most of the world, tumbled head-over-heels out of the familiar and predictable landscape of our lives into a whole new and mystifying dimension of time, space and meaning. Over the course of one weekend, I stuffed a lifetime of dreams, plans, priorities—into one of those rooms in the mind reserved for storage during emergencies—and shut the door. Adrenaline is a great organizer and energizer. It was surprisingly easy to live without the things stashed behind that closed door. My life felt cleansed of clutter, enriched by the single focus on survival and succor for the people I swept into what I would soon call my “circle of care.”

A year later, I opened the door to that room for the first time, intent on sifting through the things that were important, keeping what matters, discarding what doesn’t. Instead, I found only layers of dust, and under the dust, the torn blackened fragments of my old beliefs and hopes, their charred edges littering the floor like a scene in a documentary I saw about the inside of abandoned houses and schools thirty-five years after the nuclear disaster in the town of Chernobyl. It is as if a bomb has gone off in the last twelve months, decimating my old premises about the size and shape of the problems we face as a country and as a planet. The room is littered with the jagged evidence of our severe racial, cultural and political polarization. That I no longer share basic assumptions about what is real, what it takes to ensure safety with almost half the population of this country makes me feel as if I am in great danger. Trauma is a word tossed around in the mental health community like a fuzzy yellow tennis ball and I have come to suspect its use. But sitting here cross-legged in the ash strewn room, leaning against the plaster wall, the word feels right.

Nestled deep inside the word trauma is the word mistrust—the absence of trust—the kind of basic trust Erik Erickson pointed to as the first of the eight stages of psychosocial development. Basic trust, he said, is essential for the development of relationships and for a sense of confidence about going forth in the world. Basic trust arises from a relationship with a consistent and attuned caregiver. Donald Trump and his followers demolished my sense of basic trust in our government’s leaders and in the political system and in the citizens who follow him. Trump’s inconsistency, rage, projection and denial destabilized me every day of the last year and continues to do so into the present as his influence has, to my horror, not faded in the face of The Big Lie.

The pandemic itself was, of course, frightening. But had we had a leader like Biden to bring us through the pandemic (and the racial crisis, and the environmental crisis and the political crisis and the economic crisis) I would not be reaching for the word trauma. Trump and his followers remain, even six months after the election, an existential threat to my basic wellbeing. I hesitate to place a foot on the ground, to go forward, for fear the ground beneath my feet may give way, the path forward will be blocked by people I once trusted, some speaking a different language, pointing me in a direction I imagine will lead to a cliff, a fall, a breaking apart.

I scan my body and find in my throat not a tepid sip of weak tea languishing there but a hot flow like lava that travels to my mouth where it burns and pulses, where it wants to be transformed into sound, into a scream that holds all the fear, all the grief, all the confusion, all the anguish of this year.

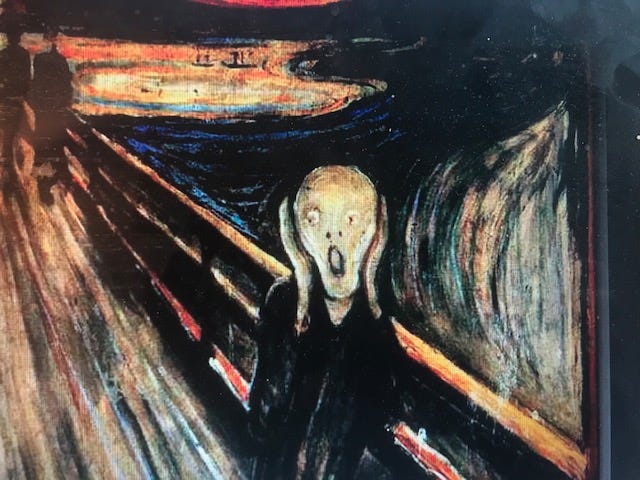

The image that comes to mind is the framed copy of the painting that hung on the wall upstairs in the hall in our old house at Porters Landing for over twenty years. I bought the print of Munch’s Skrit, The Scream, in the Oslo museum store when the family went to Norway years ago. Munch says he was inspired to create that painting “as walking along the road with two friends – the sun was setting – suddenly the sky turned blood red – I paused, feeling exhausted, and leaned on the fence –my friends walked on, and I stood there trembling with anxiety – and I sensed an infinite scream passing through nature.[2][3]”

Never in all the years it hung on the wall did I look at it and think, that’s me, that’s how I feel. But now, I recognize the infinite scream as what is throbbing in my throat, wants to spill from my mouth. Munch’s friends walked off. He was alone. He had no moment of acknowledgement for the fear and trembling he felt. But he went home and made this iconic picture and since then millions of people have stood beside him in his exhaustion and his trembling. Millions of people have felt less alone with their own silent scream echoing inside their lonely minds.

This is the part where the man on the bicycle appears. It was a few days ago that the sign came, the kind of sign that marks a turning. In the distance I saw an older man, gray haired and good looking, with a kind, round, very pink face riding his bike slowly towards me on the sidewalk. It was the day the governor announced we could all go maskless outside and I was walking, for the first time, maskless down Main Street in the college town next door. Like me, he too was without a mask. When he got closer, he spotted me and in the brief five seconds before he rode by me and out of sight, we exchanged grins, big grins that said everything—that said—it’s been a terrible year, we’ve seen unimaginable things, isn’t it a wonderful day, your face is beautiful, I love you. And then he was gone.

I think he heard the scream. Saw the blood red sky. Resolved to love the world and keep pedaling in spite of all he’d seen. After that I knew for the first time that I’d be all right, I’d figure out a way to live my life outside my small cocoon in the forest. This restless fog, the sad, frightened drift of my life, would lift.

*********************************************************************************************************

(Since today is Mother’s Day, a day to remember and be grateful to those who gave us life, I’d like to end with a bow to mine. My mother used to come up to Maine from Long Island every Mother’s Day and stay with us for the weekend while my father went fishing at East Grand Lake. She would take the grandchildren outside and hunt for four-leaf clovers in the newly greened lawn. Janet Flanagan, lover of children’s books, fond of quoting Chaucer for no good reason other than that she loved language: “Whan that April with the shoures soote!”)

Wonderful piece, Kathleen. Thank you and Happy Mother's Day.

Happy Mother’s Day!