Santa Claus and Fire

Remember the old days when, in the liminal, lazy space between Christmas and New Year’s, you made stew and thought dutifully about your New Year’s resolutions: eat less sugar, be kinder, go to the gym three times a week? Remember when this in- between week wasn’t filled with images of fire devouring miles and miles of dry prairie, entire subdivisions and shopping malls on the Front Range of the Colorado Rockies? Remember when we got vaccines last March and thought Covid was over? Remember when we’d never heard of Covid, or Omicrom or the January 6 insurrection?

“I know we’re living in an awful time, and we’re reminded of it every day… I can feel when I travel the anguish that people carry where in another time they might have been carrying hope. And I want as a writer to do something to ameliorate that anxiety because the more anxious we are the more paralyzed we become. And in our paralysis is our ending.”

I found this Barry Lopez quote in a beautiful and lyrical essay about the concept of agency written a few days ago by another Maine climate substack blogger, Jason Anthony. I urge you to read it. In many ways, my essay this week is also about agency. It is shamelessly meant to rouse you from the paralysis of this anguish filled time. It begins with Santa Claus and ends with a scarlet sun. No that’s not right. It ends with a cool poster announcing a call to action.

For comfort and reflection during this liminal week’s disquiet, I walked the snow-padded paths through the deep woods which lie just beyond the back door, sometimes alone, sometimes with Bob or our daughter and sometimes with Finn.

E.B. White had his chickens and sometimes his bad health to get his essays up and moving. I’ve got twelve-year-old, red-headed Finn and I hope someday he will forgive me. I haven’t asked his permission to share our conversations with you readers. But how would I explain myself without telling you how his heartfelt, solemn attempt to make sense of his world resonates inside my crowded mind; sets me off on a journey to interrogate old stories, imagine new ones, change the course of my life.

The day before Christmas, on a walk in the forest with his mother and ten-year-old Addie, both far enough ahead that we couldn’t be overheard, Finn turned suddenly serious and looked directly at me. “Don’t tell my sister there’s no Santa Claus. She’s not ready yet. Promise, Gigi. Promise. Let her be a kid for a little while longer.” I was a little offended, truthfully, that he’d even think I was the Santa-smashing grandma type, but I went along with his earnestness and promised. But then, the minute I got over feeling offended, I felt a great sense of sadness. Oh! It’s over for him! Last year he believed, but this year, four months into middle school, it’s over.

I remember when it happened to me. I remember the doubt I felt for a year or two about whether a sled from the North Pole flew over the house, then I remember finding a stash of presents in the attic which later got pawned off as Santa’s. That was when I knew. After that the rooms in the house seemed less bright, the mornings, less wondrous. It was the end of childhood.

That same Christmas my father laid a long string of Christmas lights out on the green wall-to-wall carpeting in our living room where the tree was set up. He left them there so long that when he took them up, a singed, yellow-brown outline of each bulb was burned right down the center of the rug. My mother, exhausted from orchestrating the magic of Christmas for five children, sat on the stairs, and cried.

But even with Santa gone and my mother depleted and often at wits end with so many children to care for, the world around me was safe and filled with the giddy optimism of post WW2 growth. It was 1957, Eisenhower was President and democracy was enjoying its successes; Sputnik, the first satellite, was launched.

And there were boys! I rushed home from school to watch teen dancers on American Bandstand and pretend I was one of the pretty girls being asked by the handsome boys to dance. Elvis Presley appeared on the Ed Sullivan show (from the waist up only!). I swooned to his All Shook Up.

After Santa was disrobed, my belief in God slipped too, for both of them were, in my childlike mind, part of the same family, so if one wasn’t real, neither was the other. But one thing did survive, until very recently, and that was the belief in the endless power and infinite presence and bounty of nature: Mother Nature.

I could sit on the steps and cry myself when I think about the world Finn is entering as he puts his own childhood behind him. Mother Nature is ill and will not be there to console him in the same way it was for me. I wish her condition was a secret I could keep from him and his sister for a long time, wish there was someone whom I could command, “Don’t tell Finn and Addie how little time is left before the planet is irrevocably harmed.” They have their suspicions, know we should not use as much fossil fuel and plastic and that recycling is good, but because their young minds are developmentally incapable of grappling with the enormity of the threat and danger, our little family here at the end of the road is careful about what we tell them about the threat.

I want to hide them in a safe place, perhaps in a deep forest, surrounded by ferns and moss, tucked away from cars and lights and noise. Oh! that’s where we are now. The hemlock are dying. There are no safe places. They will know the awful truth soon enough.

When early one August morning last summer I saw the sun rise over Eastern Bay after the smoke from the fires out West had turned that giant orb a terrifying shade of scarlet, I lost all ability to console myself with the idea that we had time, that the worst part of the crisis is a way off. There it was in the sky, a giant warning sign from the gods. Mother Nature is at her wits end.

Everything changed that morning. The very last vestige of childhood’s careless irresponsibility for what I love, vanished. There would be no long days of bridge playing, reading Jane Austin, writing poems about crows, all the while drifting slowly like a sailboat on a windless day into old-old age.

Instead, I would do what I have done for fifty years. I would devote my time to the work of healing. I would talk about fear. I would ask people about whether they were scared about what’s happening to the environment, and I would share my own feelings of fear. I would ask them to brainstorm ideas about what we could do together to change things. I would read everything I could find about how to heal this moment: about the psychology of fear, about the science of this crisis, about climate action. I would use my writing skills to tell the story of mobilizing people. I would, for the moment, give up going to my poetry writing group, give up the poetry line for the powerful sentence, the stanza for the persuasive paragraph.

It is four months later now. What I have learned is that people are very worried but unaccustomed to speaking that worry. A little tap on the shoulder, a little nudge in the direction of speech is all most people need to get started. We are not a culture that speaks of its fears. We are a culture still mired in images of the swaggering cowboy, and cowboys don’t cry. Sharing fears and asking others to help with those fears doesn’t come naturally. Nor do people feel comfortable asking someone else if she is scared. “Shhhh. It’s none of your business,” rumbles in our heads.

When we speak about fear and ask others about theirs, we are breaking the rules. I urge you all to take as a New Year’s resolution breaking the rules as fast as you can. Breaking the rules frees up energy for action. Here are all the rule breaking questions: “Are you worried about the future of the planet?” “What do you picture when you worry about the climate crisis?” “Do you feel helpless about knowing what to do?” “Do you feel all alone with this worry?” “Do you think it would help to get a few people together to talk about this and explore what we could do together?” “Do you have some thoughts about what it is we can do?”

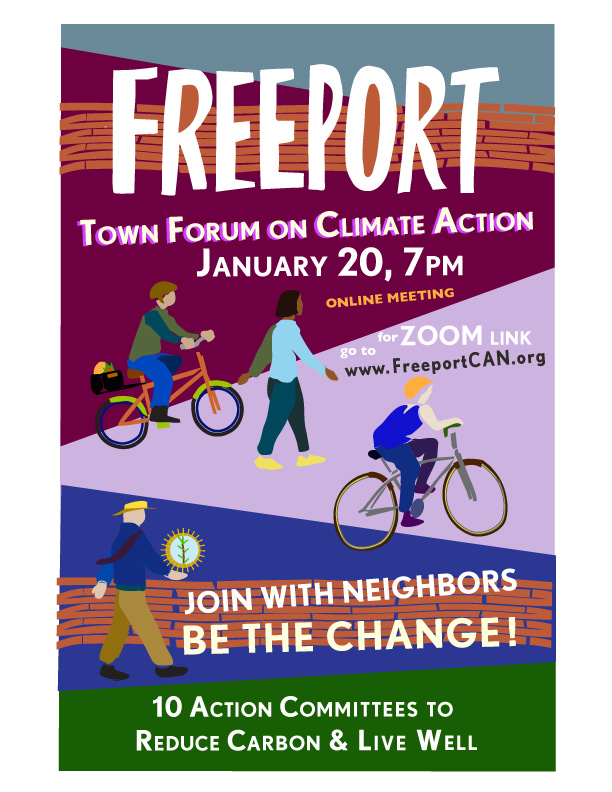

In some ways organizing for the event depicted in the poster is the easiest intervention I’ve ever made. It is as if people are waiting for a flare in the dark and, as soon as they see it, they put down what they are doing and move towards it. I didn’t start out with the idea that I would start a nonprofit called FreeportCAN, or that our mission would be to empower some people of Freeport to rethink all aspects of their carbon driven lives: what they consume and how they grow their lawns and where their food comes from and whether the cracks around the chimney are filled with foam insulation. Nor did I ever imagine that we would have ten ongoing action committees.

These forms grew naturally, like the bunchberries and the false dogwood that emerge in spring out of the litter on the forest floor. So many things have sprouted: two people who design websites, a High School boy who can help me with spread sheets and Google forms, Colin’s beautiful graphic design of the poster, money from the Town budget to pay for the first steps in developing a climate action plan, deepening relationships with neighbors and old friends, new relationships with people I’ve never met before. Friends who, like me, were slowly drifting in their own pretty boats towards old-old age are taking up the cause with vigor. M., in the spirit of play and good humor, sent this image of what our movement sometimes feels like to him.

It was all there, waiting for just a little rain, a little sunlight. Next week artists will gather in the basement, and we will make a 20-foot-long banner to announce the Forum. I don’t know where we will find the carabiners we need to attach the banner to the ropes, but now, I believe, they will, magically, appear.

So my challenge to you, readers, is: break the rules, talk about the fear of this moment, talk about the wish we all have to bury ourselves under the blankets and stay there until some Santa or golden haired goddess or technological invention saves us. Then scheme something you can do together. It doesn’t have to be ENORMOUS and it probably won’t look like what we are doing, it will be your own sausage recipe!

Someday all too soon, when Finn and Addie awaken to the trouble all of nature is in, their sorrow and fear will break my heart. My one consolation will be these words of the poet Jane Hirshfield:

Let Them Not Say

Let them not say: we did not see it.

We saw.

Let them not say: we did not hear it.

We heard.

Let them not say: they did not taste it.

We ate, we trembled.

Let them not say: it was not spoken, not written

We spoke,

We witnessed with voices and hands.

Let them not say: they did nothing.

We did not enough.

Let them say, as they must say something:

A kerosene beauty

It burned.

Let them say we warmed ourselves by it,

Read by its light, praised,

And it burned.

Thank you to my friend Jane Q. for sending me the poem, thank you to all of you, readers, who give birth every week to these words. And thank you to my new and old friends in Freeport who have been brave enough to answer the questions: Are you scared to? Do you have some ideas about what we can do? Will you help me not feel so alone with my worry?

J. Mason Morfit- true indeed

The photo of the sausage making machine was not intended to describe the operations of FreeportCAN (although it sometimes does). It illustrates a remark attributed to Otto von Bismark: "Laws are like sausages, it is better not to see them being made."