Dear Readers,

I’ve missed you. But I hope you understand why I left you last May.

Only when the coreopsis and the dogwood trees and the wildflower fields are sleeping, can I write. There’s but a few brave blooms left on the foxglove which self-seeded this year into a patch of coral wonder. It’s dark, it’s cold, it’s time to come inside, arrange words on this page, words that seek to bring some meaning and order to the fractured reality that is today’s world.

Plant by plant, all summer I toiled zestfully at bringing some order not to words but to the weedy place which was my backyard. Now a native flower garden flourishes there, risen from the dump-truck-pyramid of fecund topsoil I shoveled and wheelbarrowed into place.

Gardening some would call it. But for me that word feels mundane and utilitarian. That act of nurturing a place for blooms and butterflies and moths and salamanders and worms and crickets to flourish feeds my need to feel the pulse of life—of which I am but one heartbeat. All that life gifts itself to me, not because of me, but because it is its nature to be what it is. I am so grateful to dwell in this place with the companionship of the life forms that live beside me, dazzle me, nurture me.

Today, I will take some time to go back to the beginning of this writing endeavor and trace the themes, the characters and the events that shape my writing. It is a story of discovery, of awe, of rage, of humility and connection and above all it is a story of trying to understand the underlying mental processes, otherwise known as values and beliefs, which make up the meaning of one’s life, of my life.

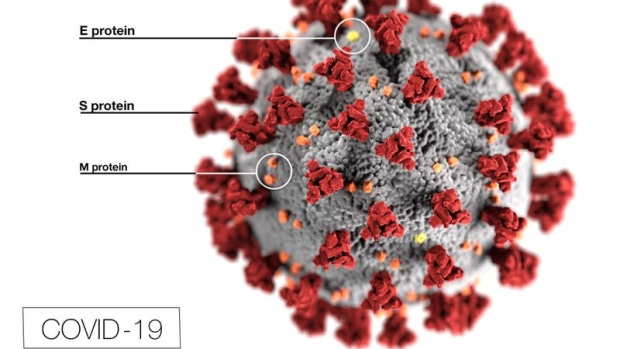

It was 2020. It was February and reports of an invisible red and gray death monster skulking on the palm of the warm wrinkled hand I’d just shaken, or on the package the UPS man delivered to my porch, shattered what little fragment was left of my feeling that Earth, Mother Earth, was, at that moment, okay.

Just months before in the dark of December, I stood on the stage at Space Gallery in Portland and introduced to a full house a new book I co-edited, A Dangerous New World, Maine Voices on the Climate Crises. The writers and artists who encircled me on that stage provided witness to our broken world and in so doing had called up the love and joy of living in this rock-strewn piney place. Standing there with them I felt both soothed and energized, fortified by the effort to waken people through art to the reality of the climate crisis and, more importantly, to action.

When, two months later, the threat of the virus crept up my long dirt driveway I thought of my grandmother, Alice Gallagher Sullivan, living in the heart of Brooklyn when, in 1919, the Spanish flu marched up her front steps and beckoned her from life, leaving my father, born in March, motherless. I rummaged through boxes of pictures in the basement and found her beautiful Irish face, with its glistening black eyes, hiding there. I set the photo on the shelf beside the masks and the hand sanitizer and summoned her spirit to help me make sense of this time. Could it have been she who inspired us to build a house here, to weave this safe cocoon in the woods?

As all this was enfolding, I was fortunate to be part of a newly formed writing group led by the sublime teacher and author, Susan Conley. Like frightened children, we opened our Zoom doors on those cold, dark Tuesday nights and welcomed the warmth and light of being together. It was in this room that the idea for my first Substack series, Process Notes of a Pandemic, arose. I needed to find language to organize my experience and I needed to find connection to others through language so as not to feel so alone. “What’s Substack?” I asked the woman in the group who suggested others might feel less alone by reading my very personal essays about making sense of the pandemic.

I wrote weekly essays all through the winter and spring but when the bunchberry blossoms bloomed in June and the vaccine was roaring inside my cells like a musclebound bodyguard, the disequilibrium in my catapulted mind cleared and I closed out my blog thinking, hoping, I could again go safely out into the world and rest in some kind of peace.

But that peace was not to last. A cop’s knee on the neck of a Black man whose last words were “I can’t breathe” was followed by a summer of protest and violence against protestors. Then the fires started to burn out West and one morning while out walking beside the ocean, the smoke from those far away wildfires shrouded the sun, causing it to rise scarlet red, as if filled not with the promise of a new day, but with the blood of the summer’s racial violence and the blood of the climate victims: the Joshua trees, the red spotted hawks, the rabbits and butterflies and too the people devoured in those flames.

For a brief time that morning everything turned blood red: the fog lifting off the islands, the wings of the migrating terns, the dew-wet sand, the rocky granite outcroppings. I felt profoundly changed as if I had received a message from the gods. “There’s very little time left, this fire is coming, if not for you, then for the children and the poor and those arctic terns whose voices you cherish more than any symphony. You have time, privilege, skills, wisdom, good health. Use it. Do something.”

I was called, that’s all I can say. Who called me? Why me? Me? But I listened and within months I was deep into organizing. I banged so hard on the door of Bill McKibben’s newly forming national organization, Third Act, that I was privileged to be there for its birth. I found others in my hometown who were worried and ready to do something, and we founded a grass-roots climate organization, FreeportCAN, which is still going strong.

And I started writing again. Word by word, sentence by sentence I tried to order the fear, the anger, the grief and the love this burning disordered world evoked in me. For a few months things felt coherent. I wept with joy when we elected Joe Biden.

Then January 6 j happened. I was working that morning and when I opened my Doxy.me screen, a man I’d seen for many years appeared, looking distraught. “Have you seen what’s going on in the Capitol?”, he asked. “It’s bad. Like a nightmare.”

That was almost 3 years ago now and the nightmare has only gotten more draconian as I watch half the country fall under the delusional spell of a mad man. I believed back then that the mad man would self-destruct and become so enraged and deranged that he’d sit inside a locked room and throw things at walls while cursing all his enemies in indecipherable monosyllables. I believed Republicans would abandon him as his lies were revealed.

I was wrong.

I kept writing. Who are we? Who is America? I started reading in areas I’d never read before. I read 1619 and An Indigenous History of the United States and the collected works of James Baldwin. I was flabbergasted at all that had been deliberately kept secret about how America came to be America and how it is that I live on this beautiful land as if it is and always has been “mine.”

I began to wonder how the politics of the moment is related to the effort to keep all these secrets hidden, to prideful refusal of some to see themselves as equal to Black men and women, to Native Americans and women and gay and bisexual persons. Savages the white colonists just up the road from me in Portland decried as they placed scalp bounties on the heads of Abanaki men, women and children. And today, DeSantis and his kin only able to feel fully human by depriving full humanity to anyone not resembling their white visages. Freedom, they trumpet from the rafters. Not for all of humanity. Only for those white men with pointy leather shoes and scowls on their faces as they conjure pictures of addicts and thieves at our border, men and women who, they declare, want nothing but a free ride and if allowed in will destroy us all.

I began to feel a terrible sadness and emptiness come over me when I walked the land. I heard the spirits of the silenced and erased Wabanaki men and women and children who walked this land only a few generations ago whisper to me. “Tell our stories, bring us back to live among you. We are all kin.”

I wanted to feel that kinship to the people who lived on this land before we white settlers arrived and in the blink of an eye undid 10,000 years of indigenous ecology that preserved the ecosystems around me, that understood that the white pine and the deer and the sweetgrass were talking to us, were alive and offering us life and sustenance and needed to be treated with respect and care.

I read Wabanaki legends for instruction. The story of “Grandmother Woodchuck” struck me as the one story which epitomizes the difference between our capitalist worldview and the kinship worldview. Just tell that one story to children when their minds are being formed. That one story can save us.

Little did I know that four months after I read it, I would stand on my back porch facing the forest which had been painfully silent and listen to Dwayne Tomah, a Passamaquoddy storyteller and culture keeper, read a story to me in Passamaquoddy. “Do you know what the name of that story is?”, he asked me when he finished his reading.

“No, tell me”, I said. It’s “Grandmother Woodchuck”, he replied.

And then three weeks ago Dwayne read that story in person in front of a crowd of over a hundred people here at the Wolfe Neck Center. I met Dwayne this summer at a conference and invited him to come speak to us. The title of the talk was “Wabanaki Stories to Live By in the Time of Climate Emergency.” Dwayne shook everyone’s hand in that room. Looked them in the eye. Made connection. When he recounted the Grandmother Woodchuck story the audience was spellbound. “Together we must save Mother Earth. We aren’t listening to her. She is dying”, he told us.

Inspired, uplifted, nearly jubilant we all stood at the end of his talk and cheered him. I drove him back to where he was staying that night feeling a great joy that his presence here made these woods come alive again with story and ancestors.

I went home and climbed into bed. The buzz of a text message disturbed the peace of the room. Probably someone texting to say how great the evening was, I thought to myself. I reached for the phone. It was my daughter. “Mom, there’s been a mass shooting in Lewiston. The shooter hasn’t been found. We are all on lockdown.” Lewiston is 20 miles away. “Are the door locked?”, I asked Bob.

The warning texts, the news reports, the closed markets and empty streets the next morning, the kids kept home from school for two days. “Maine, the way life should be.” Like a looking glass image: shattered. Gun sales in Maine soared. I look in mirrors and am surprised to see that they aren’t shattered, that the image I see of myself in the glass is intact. I don’t feel that way. I feel like there are cracks everywhere: in my mind, in my heart, in my sense of safety, in my sense of coherence. Who are we? Who am I? How should I live?

I haven’t even mentioned Israel and Palestine. Or the Ukraine. Or the fact that in one week the government will likely shut down because extremist Republicans, who now seem to encompass almost all Republicans (my father, a good Republican would, I hope, if he were still alive, be appalled) want to destroy our government. Or this from the New York Times just four days ago:

“In 2030, if current projections hold, the United States will drill for more oil and gas than at any point in its history. Russia and Saudi Arabia plan to do the same.”

How do we hold all this? I know I cannot do this in silence and alone. This is why I write. Many of you may want to turn away from this accounting. By next year we could elect a man who is in jail for inciting a riot to overthrow the government. I imagine if that happens, there will be civil war. While all this is happening, we are still on a very short timeline for preserving a climate that will allow us to thrive.

What is required of us in the face of all this? What is required of elders like me? Do we have a moral responsibility to the children whom we have always been drawn to protect and whose future we have imperiled by our own success? What concepts of self and other do we need to examine to make decisions in harmony with the needs of life? What stories about what makes a good person, and what brings happiness and meaning to life need to be reexamined? How do we live the new stories?

I haven’t got much time left. I am old. A year and a few months and I will be 80. But in some ways, I feel like a child newly born into the world. I got most everything wrong about what it means to be human in the first eight decades. It’s time to erase all those assumptions and look at the world anew.

I remember all the questions my grandchildren asked when they were small, and their minds were taking in this place called home. Where do you go after you die? What is this rock? How does the moon rise? What is this purple flower called? How many different species of moss are there? Why do birds fly?

It’s time for wonder to return. And out of that wonder perhaps I will have some stories to pass on to my grandchildren and those coming up behind me that will leave them in a different place when they get to this place in the road and look back.

I am with you on all counts. I live in western Maine, in a tiny hamlet, in the woods, I have watched everything you say as it unfolds, thinking the same things.

First, I want to say there are organizations for reparations for the Native Americans, e.g., LANDBACK and First Light (https://firstlightlearningjourney.net/).

I've been thinking about all the issues you're talking about probably my whole adult life. I was an activist for decades and found that once you get to politics, people's attitudes are set in stone, you can't move them. The Vietnamese monk Thich Nhat Hanh discovered this in the '60s and changed course to address people's core values, on an individual basis, and I do think this is the best way but it's a very slow process, as people will only change if they feel a need to change. The real war is cultural and it has to do with our narratives, and narratives have to do with community. If you change your mind and reject the narratives of your family and friends — your "tribe" — you risk ostracism or worse. It can be dangerous to change your worldview and people sense that at a deep level so most have tremendous resistance against changing it. I have spent my life working on how to overcome this resistance.

I have found that most people I've met on the left and right agree on most basic values, but their narratives of how to get there could not be more different.

You must know the Native story about the man with two wolf pups, one evil, one good, which will grow bigger? the one he feeds. Trump's popularity comes from the fact that it's easier to destroy than to build, easier to deflect blame onto those already marginalized and powerless than to fix power hierarchies and systems that ensure the poor and powerless stay poor and powerless. Easier to disrespect and destroy than to respect and nurture.

And it comes down to two worldviews: kill or be killed vs the rising tide raises all boats. Destruction vs nurture.

If people think you're trying to change their worldview, they shut their ears and you're locked out. If you want to change them, you have to avoid all triggers and meet them at a point where you can agree, and then work from there, subtly. If you're a cultural warrior, you can change minds, but you have to avoid codified terms and tropes, which are land mines.

Really the right medium to use is film but I'm not a filmmaker. The reason why film is so good is that you have the time to build a story gradually, lead your viewer in gently. Fiction would be just as good if more people read but most people don't read. Songs can be effective but mostly at giving heart to the choir. Same with photography. I'm a painter and my whole life I've been fighting the good fight but what I find is that with a still medium you have to be very, very subtle so as not to throw up your viewer's defenses. I am trying to open a crack of empathy, a crack of doubt, so the words of someone who uses facts, a historian or a journalist, can widen that crack. Most of the painters I know simply reinforce the status quo.

The world likes its hierarchical structure as it is thank you very much and does not want to change. Way more people cooperate in their own and others' dehumanization than try to do something about it, because the punishments for waking up are draconian.

I think something terrible is coming, massive death and destruction, but that small bands will survive, and that the survivors will be the ones who help each other, and help the planet heal.

That Natives know this. They've seen it before.

Nice to know you're out there, an ally.

Grateful for your Presence, once again.

With you, your Mother spirit, this earth. Thank you for locating the words and the action.