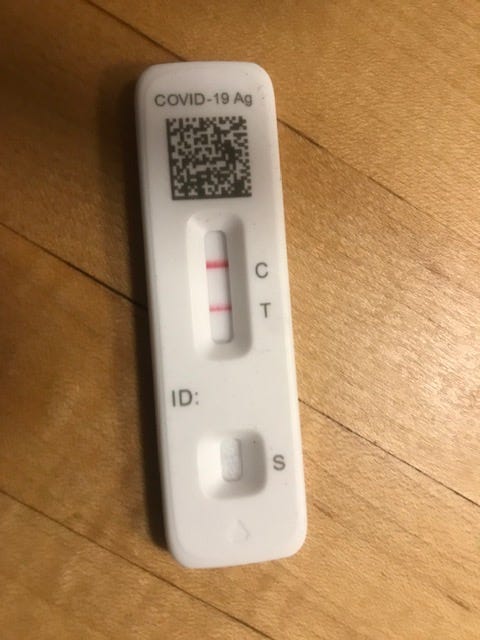

“Stop, I have an idea about we can do on our walk,” said ten-year-old Addie. We are deep into the woods by then, the snow underfoot hard and stippled with the frozen footprints of deer, squirrels and the few two-legged creatures who’d walked the remote Tadpole trail since the last snowfall. Biden has not yet said, “I will allow no one to place a dagger at the heart of democracy.” It is mid-day Thursday, January 6, the one-year anniversary of the insurrection in Washington D.C. and it is a school day, but the kids aren’t in school; it is a workday, but Bridget isn’t working. It has been three days since the line on each of their test kits turned pink: the color of covid.

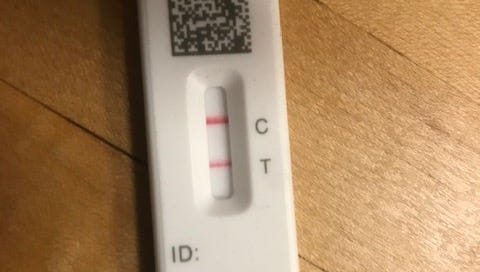

Bob has not joined us for the walk. He is at home, in bed with a low fever. And a pink line on his test. The lines on my test remain gray, unchanged. There are now five breakthrough cases in our double and triple vaccinated family.

Neither the grandchildren nor my daughter or our son-in-law is very sick. “I feel like a really old man with a bad cold,” Finn said leaning on a walking stick he’d just broken off a newly toppled white pine whose trunk was riddled with rot. “How old is that?” I asked. “Fifty,” he said. “I feel like I’m fifty.”

The four of us stand in a close circle on the trail to hear Addie’s idea. I have a mask on, but we have all decided they don’t need a mask here among the mossy boulders and the white pine and the hemlock where we rarely ever see another person. “Let’s all tell a story about something really embarrassing that happened to us,” Addie suggests. Everyone’s up for it. We come from a long line of Irish story tellers. And Irish secret keepers.

The story of my grandmother, Alice Gallagher Sullivan’s death on Carroll Street in Brooklyn from the “Spanish Flu” in the pandemic of 1919, two weeks after my father was born, is a story kept secret for years and years. The secret bullied its way through time, conceivably, I wrote last year when I wrote The Covid Diaries, influencing our decision to live together here in the forest where we would be safe, I mused last year, when the next pandemic arrived.

I tell you all this so that when you hear the story about my most embarrassing moment you will have some sympathy for me. “You go first, Gigi,” Addie directs. “Oh, that’s easy,” I reply. “I have a story that happened early this morning and I am still sort of mortified and I haven’t told anyone about it but Gigi Bob.” “Tell us, tell us.” They are all ears.

“I got thrown out of Bow Street Market this morning.”

It began this way. I left the house before eight so I could get to Walgreens in Yarmouth, the next town over. I’d heard they had test kits and, test kits being in short supply everywhere and omicron spreading like the wildfires of this climate-desiccated year, I wanted to get there before they sold out. I hadn’t been out of the house in days, the sun was blindingly bright as it hit the ice crystals on the trees and transformed the five-mile trip into a blazing hallucinogenic light show. When I got to Walgreens, five people were already lined up at the cash register, boxes of test kits gripped in their hands. “Are there anymore?” I asked a customer anxiously.

She pointed to a rack filled with rows and rows of test kit boxes. No sign warned there was a limit on the number we could buy. I took four to the checkout counter, so grateful to find them. I thanked the cashier and told him to tell Walgreens what a good job they are doing.

Filled with warm feeling and exuberance, I got back in the car and headed home. A text from Bob dings its way into the moment. “Stop at Bow St. Get me yoghurt.” No please in his sentence. I don’t like grocery shopping. Bob, on the other hand, has strong connections to the hunter gatherer strain of his tribe and happily greets the shoppers he knows and the shoppers he doesn’t and comes home with bags of potatoes and pears and nuts and places them proudly on the kitchen counter.

“Don’t we still have some in the fridge?” I text back. “Just get some,” he replies. I shouldn’t begrudge the sick man his request, or his failure to say please, but the thought of going to Bow St. has unsettled me, deflated the morning’s red balloon of exuberance. I am a little agora phobic of crowds these days. Did you know that agora is derived from the Greek word for marketplace?

It is not yet 8:30 when I get to Bow St. The parking lot isn’t crowded. I am relieved. I put my mask on and go inside expecting to be there for only a few minutes, but the vegetable isle beckons. I can’t resist a blood red beet or a pocked orange sweet potato. The tall gray-haired man stacking these edible pleasures has his back to me. When he turns around, he smiles at me. His smile is the smile of another time, a pre-covid time when smiles were easy and free. He is unmasked.

I get that funny rushing in my head and down my arms that I have enough wits about me to know means my amygdala is flooded and my neocortex, the part of the brain responsible for judgement, is awry. This little bit of insight doesn’t freeze my tongue, get me out of the store and safely back in my car. But I am still rational enough to search for language I teach other people to use, language that isn’t designed to be hurtful. “I feel very sad when I see you aren’t masked,” I tell the man whose smile now goes from innocent to stunned. “I feel like you don’t care about me or about our community. If you cared, you would put on a mask.” I start to cry. He turns away like a cornered cat.

If the story ended here, you might feel a lot of compassion for me. But it doesn’t. After the vegetable man turns away, I notice the change in me. My sadness is still there but the Irish fighter in me is now the one walking the aisles. I head for the yoghurt section at the back of the store and pass two more employees not wearing masks. This stuns me. This place, Bow Street, is a place that has always cared about the community. It is owned by a family who has lived in this town for generations. We who have lived here for a long time all have a story about packets of kindness distributed like free samples of jam to its customers.

At the back of the store, more unmasked people. I notice that there are more unmasked customers than masked ones. A big man, way over 6 feet, so tall I have to raise my chin high to look into his uncovered face, chuckles at his unmasked wife. Now there is no filter on my fight or flight response, on the hormonal burst coming from my amygdala. I walk up to the towering man putting eggs in his cart and say the same thing to him I said to the vegetable man. I try to modulate my tone so it sounds matter of fact and as calm as I can get it given my racing heart. I stand there and wait for his response, a small part of me still able to have a little understanding that this poor unsuspecting fellow has just been accosted by a wild-haired raving old lady. But he’s a fighter too and doesn’t turn away.

At full height, in a very loud mocking voice that can be heard by all the customers in the aisle, the man says,” Have a really nice day, young lady.”

Well now I am truly lit like a Fourth of July rocket. “What you really mean,” I say, “is fuck off, lady.” I don’t stop. “Same to you, sir. Fuck off!” Customers stare. I pick up the container of yoghurt, head for the check out counter.

On the way there, I pass the meat counter in the front and center of the store, the place specifically and brilliantly designed by the owners to be a place where people gather, like an old market in a square. Four men, slicing steak and packaging sausages. None of them masked. I stop in front of the counter, tell them that I am disappointed they aren’t wearing masks for they set a tone of care and responsibility for the whole town. Poor fellows. They stare at me, frozen in the act of cutting, their knives poised above the meat.

Okay, I say to myself. Do this the right way. Ask to talk to the manager. After a big scurry, everyone by now looking at me like I am a madwoman, the granddaughter of the original owners of the store, now the manager, is fetched from the back room. She looks scared. I tell her too that their store should lead. I remind her that the teachers are hanging on by their fingernails, that the data about kids’ mental health reveals anxiety and depression is spiking in that cohort, that hospitals are understaffed. “We all need to do our part to get this under control,” I say, my anger turning back to sadness. I start to cry.

She tells me the store is following CDC guidelines and customers don’t need to come to the store, they will deliver. I tell her that isn’t enough. I expect more of Bow St. She stands there looking at me, no longer speaking to me, while I try to check out. The unmasked cashier whose face is inches away from mine, scowls at me; my hand shakes as I try to put the credit card in the slot.

The towering man from the egg department has moved to the deli counter, 30 feet behind me. I look up and he is staring at me. From across the room, his voice loud and sodden with irony and what he thinks is the victory of the last word, he shouts, “Have a nice day, young lady.”

I don’t miss a beat. “And fuck you too,” I shout back.

That’s when the manager asks me to leave the store. That’s when I leave.

“Oh Gigi,” why did you do that?’ the kids ask after hearing the story. “Because that’s just who Gigi is,” replies my daughter, a woman just as fierce as I, but infinitely better at controlling her temper, at remaining composed and articulate. “Wow, Gigi, I hope they let you back in!” the kids said. I hope so too. I hope no one recognized me. I hope, like the Lone Ranger, people will ask, “Who was that masked woman?”

“Okay, time for you to go next, Addie said to Finn when I’d finished. Relieved none of them loved me any less after I told them my story, we kept walking through the forest, telling stories, loving each other.

I’ve apologized to Bow St. in several emails I sent since Thursday. I apologized for my language and for scaring whomever I might have scared. But I kept up my plea for their leadership on modeling how we care for each other. No one has answered any of my messages. By Friday, when Bob’s fever lifted, and I stopped worrying he might get really sick and have to be hospitalized, again. I urged him, levelheaded town leader that he is, to email Bow St. and make the same requests I’ve been making. Friday night he got an email back from the owner.

“As of Saturday morning, January 8, Bow Street will require all its employees to wear masks.”

Congratulations and hip hip to Bow St! Yesterday, in the bright blue of the early afternoon, I went back to Bow Street for saltines and broccoli for Bob. Every single employee was masked. 99% of the customers were wearing a mask. I felt entirely safe, well cared for and grateful to Bow Street for listening. And for one more time, I cried.

There is one small bruise I carry from this experience. Its origin lies in a detail at the end of the story. Do you see it? It is my husband, the well-behaved man, who is acknowledged when the change comes. I don’t begrudge him this one wit! But my own efforts, bungled and messy, as well as my apology, have been met with silence, the ultimate shame inducing weapon. I am all too familiar with this silence. But age, oh age, has taught me that there are tribe members who won’t cast me out of the cave and into the dark night alone because my fierceness makes me too loathsome to belong. Fierceness is now a quality necessary for our species’ survival. I can feel the tribe around me cheering on the Irish fighter who lives so close to the edge. Thank you. I am deeply grateful.

I am taking an online substack writing workshop with George Saunders, the master of short stories. A good story, he tells us, is one which embraces the complexity of a character, her conflicting motivations, and actions. Though a short story is set in a certain time and set of circumstances, it also transcends that time. A good story is never one thing, George says, it is many things.

I hope this story of the Masked Woman passes some of George’s requirements for a good short story. While you can read this story as a story about this wave of the pandemic, you can also read it as a story about the climate crisis, or as a story about the threat to democracy. I hope you read it as a story about the different and flawed ways each of us copes with this frightening moment in time, our behavior so influenced by our past, our family secrets, our inherited dispositions, our age, our ethnic background. And I hope you will read it as a story about love.

Thanks so much for posting this. I posted a very polite request on Bow Street's facebook page asking them to require their employees to wear masks. They deleted it immediately, no response to me (I bought our house from the Nappi's and have served with Sheila on a couple of boards). I haven't been back there in 2 weeks, and live a 10 minute walk away. I hadn't heard they started requiring masking. Thanks to you!

This is brilliant Kathleen! You are my hero. Miss seeing you in our neighborhood. Good health to all Sullivan Stevens gang and much peace and ease as you move into 2022.