Winter, Covid and the Owl

Freeport, December 6, 2020

Like a giant black wave, the dark, winter isolation of covidlife has arrived. Dr. Shah has called the virus’ behavior here in Maine, “ferocious.” Though inside the circles of my life my family and I are as safe as anyone can be at this moment, I know that just on the periphery we are surrounded by great fear and suffering. In a pocket of my mind, I carry the melancholy of that knowledge like a heavy stone. I spend almost all my time at home. This morning the electricity is down after last night’s storm. Ice and a thin layer of snow coat the porch, all I can see of the world at 6 am this morning.

In winter here at the end of the road there is endless silence interrupted only by the calls of the small birds. No cars go by, no people appear, no light but from the moon jabs the dark night. The trees have given up their summer garb, and the grasses are down to drab browns and the tall asters are spindly spires of decay. Even the artillery fungus hiding in the mulch that shoots tiny dots of black spores onto the windows and the white siding has quit its assault and gone quiet. At the feeders, there are no surprises: the same chickadees, nuthatches, tufted titmice, vie for the sunflower seeds and the peanut suet. The hummingbirds and the warblers and the white throated sparrows have all left.

When I do get in the car and drive out of the circles, there is no place to go, really, besides the few doctors’ appointments I have and an occasional trip to the grocery store. Even the local bank where the tellers once greeted me with a smile and we caught up on our new hair styles, has closed its lobby and is only open for drive through banking. And honestly, going to the grocery store just breaks my heart. I never realized that I went there with a hunger not just for the milk and chicken, but for faces, for the smiles of recognition with neighbors, for the nods of understanding when a child wedged into the cart of the woman beside me is fussing for something forbidden. I want to weep every time I come out of the grocery store for the hunger I feel for human contact of the most ordinary sort.

This winter there will be no holding the grandchildren’s hands as we rush across Congress Street in the winter dusk, breathlessly take our seats in the big auditorium just before the curtain rises on this year’s Christmas Pops Concert. There will be no Christmas fairs: makers tables set up in the old factories across the river in Portland, selling everything from jalepeno and lime spiced salt to scarlet felted scarves; no Sparkle parade on Maine Street when we huddle on the curb with cold feet until Santa arrives perched on the back of a fire truck; no Christmas parties where I dress up in a red satin skirt, stand around with a pink shrimp in one hand and a glass of sparkling water in the other and make party small talk.

In the dull, sensory deprived tank that is covid life, I am beginning to hallucinate. I am in the cavernous terminal at Grand Central Station, where my grandfather owned a bar (a bar!) and there is a massive wreath over the clock and I am standing in the middle of all the commotion while maskless men and women drift by, laughing. The word assignation comes to mind and I am not afraid. And in the subway tunnels there are buskers with guitars and saxophones and the music makes my feet dance and I keep walking, down 5th avenue and there is Macy’s and there are the windows crammed with Christmas dioramas of luxurious rooms which make me long for a past I never even had. I want to hug everyone: the man begging on the corner of 5th and 42nd, the fat, maskless Santa on Park in front of the Waldorf Hotel, the stern looking Salvation Army woman beside him in her uniform ringing her bells for the poor.

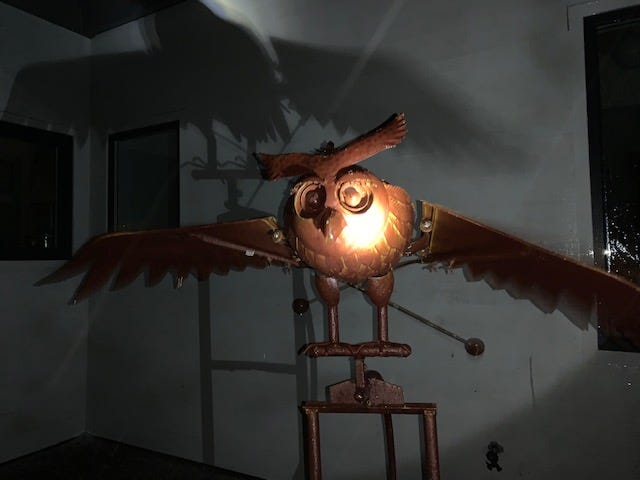

It was in this state of mind that I saw the owl. He wasn’t flying because there is no wind inside Skillings Greenhouse. I wasn’t sure what all the counterweights were that hung from his iron wings, but I was sure I had to have him. “We’ve been selling them like hotcakes all summer,” the manager said. “This is our last one.” “I’ll take him,” I said, surprising myself with my certainty. With the owl stowed in the back of my car, I was suddenly lifted out of the fog of covid and excited, even thrilled, confident this brown metal beast with the fringed lashes and bulging eyes would get me through the winter with its ocean of dark and the frightening shapes that swim inside it.

Reality needs a little bending in these bizarre and frightening times. A little escape down 5th Avenue, a little magic. The Romans believed the owl of Athena would protect them. They nailed a dead owl to the door to avert evil. My owl is set in the dirt just outside the kitchen window, watching, vigilant. When the wind blows, her wings flap and her head moves up and down as if asserting some promise. We rigged a spotlight to shine on her after the sun deserts us, which is all too early this time in December, and now, like the owl, we too can see in the dark.

Why didn't I see that owl first? I would have snapped him up in a minute! What a perfect impetuous purchase!