The day my heart broke, again, hard, crying hard, there was still snow on the ground from the snowstorm that gifted us for a few days last weekend with the joy of winter, real winter. The immense storm that blasted the coast of Maine last Wednesday with heavy rain and wind, washing out roads, tearing docks and fishing shacks and seaside cottages from their moorings and thrusting them into the sea like children’s skipping rocks, had not yet arrived when my husband came in the door with a charcoal covered sketch book in his hand. “Addie wants you to see these drawings,” he said handing me the book. “I passed her on the road driving in and she gave me specific instructions to tell you to look at the pages she’s turned down.”

Addie is 12 and she’s our granddaughter and her brother, Finn, is 14: middle schoolers both. The bus drops them off at the end of the dirt road that winds its way to their house before it gets to ours, .2 miles later. They are exactly the same height, though soon a growth spurt lurking in their bodies will surely bring their eye-to-eye encounters to an end. They both have red hair and loud laughs and, on their long walks home through the woods, they jostle each other like little prizefighters in training. And when there’s snow on the ground there’s bound to be snowball fights and ice slipped down a jacket and attempts to flip each other into an unsuspecting snowbank.

Addie has given me permission to tell you this story and show you what’s on those pages. “I am too shy to do any public speaking,” she told me a few days later when we found time to talk about what I found in the dusty colored sketch book. Addie has lived more than half life in this remote nest in the woods. Her playmates are the speckled salamanders who live under the rocks, the tadpoles who swim in the streams, the pileated woodpeckers who drum on the hollow trunks of dead spruce, the owls who hoot in the still-dark dawn. They are her friends, her family, her kin. If she were to say she loves me as much as she loves a writhing pink worm newly uncovered in the garden, I would be honored.

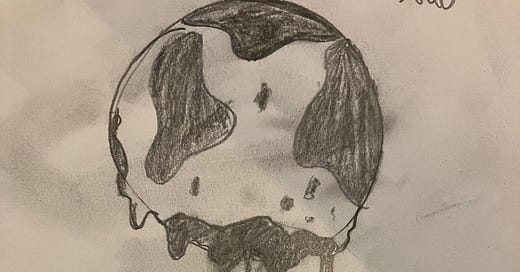

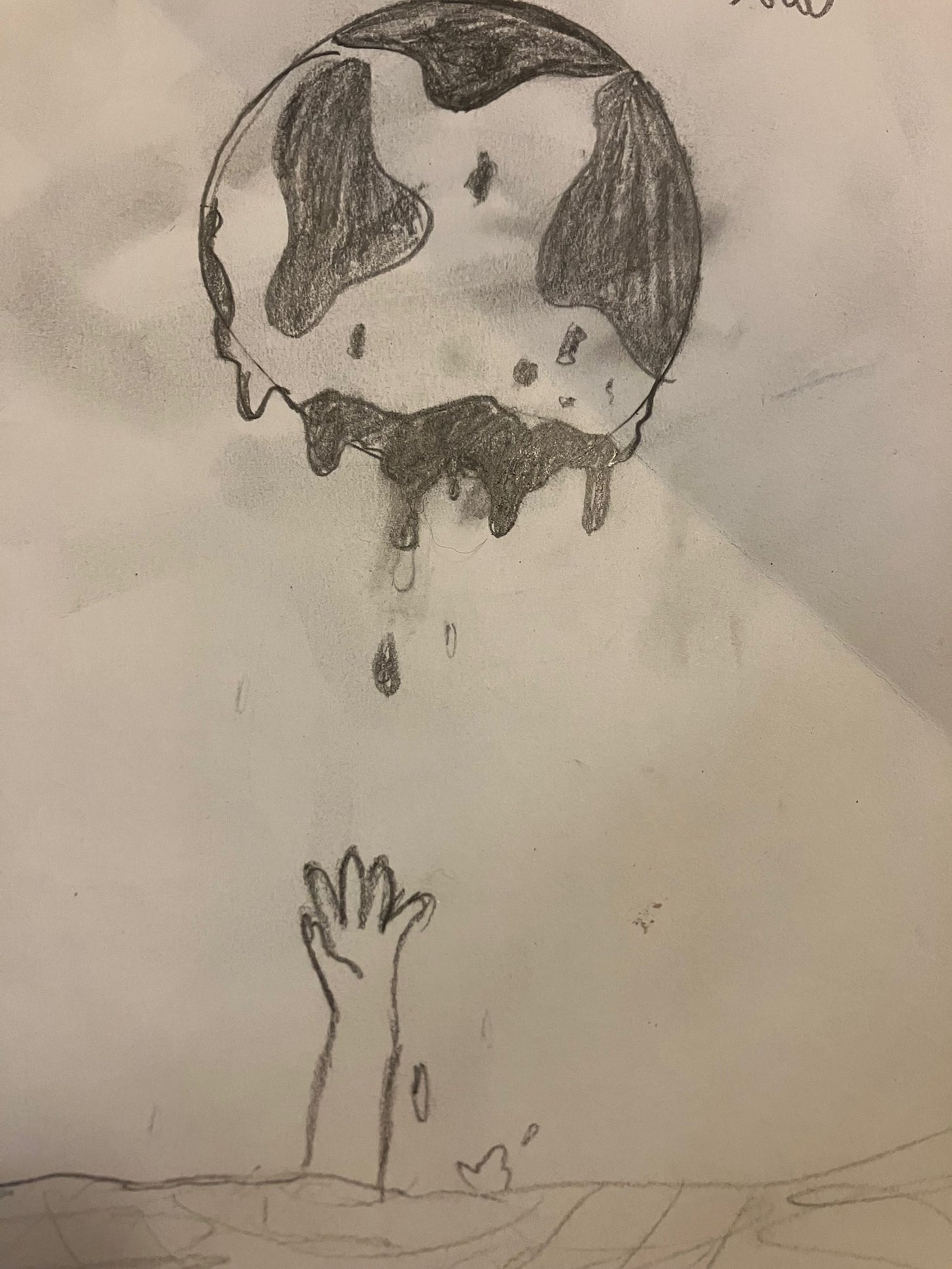

It was almost dark when I sat down to open the book, anticipating another iteration of the purple woodchuck she gave me for Christmas, or perhaps one of the silly human-monster faces she draws, some of which uncannily resemble me! I opened the book, found the first turned down page. Then I saw the arm rising from the water, the open hand pointed at the drowning world, shedding her tears into the sea.

She knows. The title she gave to this drawing is “The World is Drowning in Its Own Sweat. “

Oh, my heart. Oh, hers. Oh, the children.

As a family we all agreed that it was important for Addie and Finn to come to this terrible truth in their own time. We wanted them to have an experience of the unbroken earth, of childhood wonder and delight that was not bound up with fear and grief.

But now she knows.

And she wants me to know that she knows. And she knows too that I know because she was there in the crowded Town Council room last March when, to my surprise, I was given an award for my climate work in town. When I rose with a shaky voice to accept, I turned to her in the audience, sitting in her chair beside her mother and said, “After I am gone, I want my grandchildren to know one thing. I want them to know that I tried.” Since then, Addie’s never mentioned my pledge to her or inquired about it.

Until today.

The last time my heart broke this way, felt this kind of deep-earth pain was when Addie’s mother, Bridget, was in the third grade. I was at home siting on the same red velvet couch that Addie will sit on when we talk about her drawings. Bridget had just gotten off the bus and come into the living room looking shaken. “I am worried I will have to ride my bike underground. All my friends are worried too.”

She’d just learned in science class about the chlorofluorocarbons, or CFC’s, in Styrofoam and how they deplete the ozone layer, making the sun’s rays more dangerous. I remember the cold rush of fear in my body, followed by a rush of energy and conviction to do whatever I could to make the earth a safe place for her.

It’s a long story and many of you already know it, but together with teachers and students and mothers and fathers we did do something. We banned the use of Styrofoam here in Freeport and motivated many other communities to follow suit.

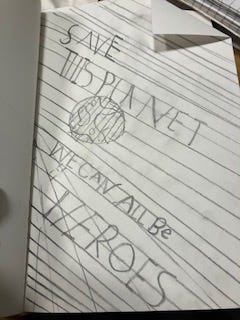

I turn the page and there it is: an image that embodies that same rush to act, that movement from recognition to action, from devastation to mobilization. “Save the planet. We can all be heroes.”

When we meet in person several days later, I am aware that her mother has spoken with Addie about how she’s coping with this knowing and am reassured by both her mother and Addie that she’s okay, that she doesn’t feel deep despair or stay awake at night worrying.

“Are you learning something at school about climate crisis or talking to other kids about it?” I ask her, curious about what precipitated these drawings. “Nobody talks about it,” she replied. “We’ve never talked about it in class and none of the kids have ever talked about it either.” This is her first communication about it to anyone.

I share my own experience of feeling isolated with my fears about the planet which prompted the formation of FreeportCAN and how much better I feel now knowing there are others in my community who care. I tell her how important art is to the climate action movement and assure her that her art is very compelling, that her images can move hearts and minds to care and spur people to be Heroes!

She hasn’t to date shown any interest before in the book I co-edited in 2019, A Dangerous New World, Maine Voices for the Climate Crisis, but when I take it off the shelf and show her the beautiful art paired with poems and essays, she is curious and excited by the idea of art in a book. She wants to see what I wrote, and I can feel her pride in me for pulling that book off.

“What about a book, Addie?” I ask. We could edit together a book of writing and art by kids, call it A Dangerous New World, Children’s Voices on the Climate Crisis. She loves the idea. My mind races. We could get a grant. We could put out a state-wide call for kids’ art and writing. We could ask the publisher of DNW if they’d publish a book like this or we could self-publish. I wish there were four of me.

Who can I get to help with this?

A piece in the Climate Coach column of the Washington Post this week confirms the importance of the kind of art Addie is making. Potential Energy, a marketing firm co-founded by the director of the Harvard Center for the Environment and a Marketing Professor at Dartmouth College recently tested different climate messages with about 60,000 people in 23 countries representing most of the world’s population. The most effective, most motivating message?

It’s not fear, it’s not rage, it's not hope. What the evidence points to is:

What tends to motivate people is when they think someone they love is threatened,” … That's programmed into us. You act because you care about someone you love.

Or if you are like Addie and have come to see the tadpoles and owls as kin, or like the Native Americans who see Mother Earth as a living relationship they have a reciprocal relationship with, you act not just because your grandchildren’s lives are threatened but because the lives of all the living beautiful things that fly and squirm and flutter and wiggle and divide and inhale: all of it is threatened.

When I told Addie just before she left that I will pass her art and her message along to all of you, readers, she gave me a big hug and thanked me. I watched her as she walked down the driveway and I could have sworn she’d grown a few inches taller in just the short time we had together.

Beautiful story Kathleen, and beautifully written. I feel strongly that your writings also ought to be compiled into a book to be published and widely dispersed. You are a voice and a spirit for hope that the world is possible to save . Thanks, as always, for your compassion and caring for the world we have.

On a personal note, the devastation at our local Higgen’s Beach after the two recent storms is emblematic of our new encroaching norm. So sad for us, so much more for the children and children’s children who will come after us!

indeed, it is a beautiful thing that we live with and through our children and grandchildren...chuck