Five days from now, the moving truck will turn off rt. 1 in Columbia and head south for ten miles. The truck will cross ice coated salt marshes where, perhaps, a flock of geese are gathered, or a herd of deer; it will bounce and up and down the rolling hills of East Side Drive; pass the hulls of old fishing boats, the frames of rusted out cars, abandoned houses with crumbling roofs, the blue glint of Pleasant Bay appearing and disappearing on the right. Too soon will the truck pull into the driveway and I will watch from the kitchen window as the moving men get out of the truck, survey the view of Eastern Bay across the field, the pitch of the walk up to the house.

How many hours later will everything in this beloved second home be gone — the twenty-five or so boxes of sad, irrelevant stuff, the floral rug from Anthropologie, the many paintings and prints on the wall, the oak dining table I bought in 1972 when I answered an ad in the Chicago Tribune and a farmer, down on his luck, drove two hours to the city, wrestled the table up the stairs of my apartment in Hyde Park and left it behind?

When we walk out the door next Saturday, there is, however, one small thing we will leave behind: a tiny 3” hand carved chair which sits on the top of a window frame a few feet from the oak table. We will leave it there to whisper its inspiration of change and hope into the room and into the future.

“Can you tell us the story of that chair?” the new owners asked when we met at the house a few weeks ago. “It caught our eye right away,” C. said. “Oh! my grandfather made that!” I love telling the story of my grandfather, Thomas Flanagan, whom I called Pop-Pop, and his tiny chairs and am moved that among the hundreds of artifacts strewn throughout the house they could have been curious about, it is the delicate three inch wooden chair with the pinecone patterned oil cloth covered seat which captured their imagination.

The story of Pop-Pop’s chairs and the miniature pictures of farms and waterfalls he painted is a story about the dark side of rapid economic growth and one man’s brave choice to step aside from the twentieth century’s dream of expansion and progress as the key to happiness.

My grandfather grew up on the grounds of the Brooklyn Navy Yard, not the Brooklyn Navy yard of todays’ hip entrepreneurs, but the early 1900’s Navy Yard of giant docks and cranes and steel battleships and machinists and ironworkers. His father, Jeremiah, my great grandfather, was the Commandant of the Yard and I have a picture of him with his twelve children lined up in front of the columned porch of the house. I don’t know how Jeremiah managed this kind of success in a city where signs saying “Irishmen Not Apply” appeared in windows. But success it was! Jeremiah even owned a house at the Jersey Shore where my mother visited her grandparents when she was a child.

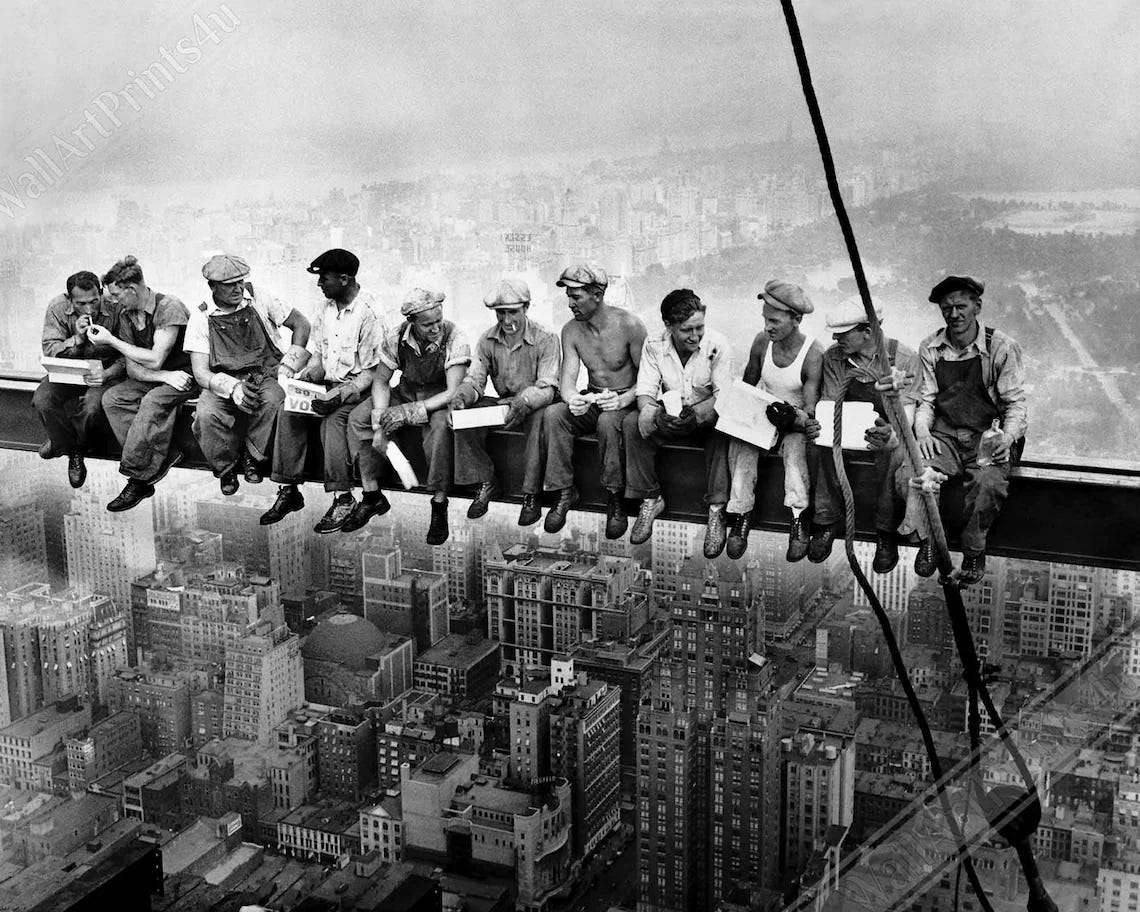

When it came time for Pop-Pop to find work, he got a job working for Traveler’s Insurance as a safety engineer. His job was to keep men safe: the men who built the giant skyscrapers in New York City’s race to the top. There were then no safety codes; there was no OSHA. Men died and were injured at terrible rates and there was nothing my grandfather could do to save them. He worked at this job for thirty years. But the toll on him was great, and, my mother said, caused him much sorrow and worry.

So he quit. He gave up his own rush to the top, his desire to accumulate status and the stuff that goes with it and retired at age 50. He moved his family to a small bungalow beside a farm populated with cows in North Merrick, on the South Shore of Long Island. He set up a workshop off the kitchen that smelled of turpentine and oil paints. His work table was lined with containers of small things: carved pieces of bamboo, jars of paint, 6” canvas squares, paintbrushes, glue. In that room he carved small chairs and small pianos and painted tiny landscapes. And soon, he began to care for small grandchildren, one of whom was me. He taught me how to whistle with a piece of grass between my fingers, how to play mumbly peg with pen knives, how to find delight in marsh grasses and baiting fish hooks with wriggling little fish he called killies.

My grandparents had one car, a small house. They bought very little. The seats on his chairs were made from strips of an oilcloth I remember from when I was a child and my white lunch plate filled with a bologna sandwich accompanied by a handful of Wise potato chips and sweet Heinz pickles sat atop that cloth.

This is the story I told the new owners of the house. “Oh!” C. said. “My grandfather was one of those ironworkers building those skyscrapers at the same time as your grandfather was trying to keep them safe. Who knows, maybe your grandfather kept mine alive?” So, the chair will stay behind as tribute to both of our grandfathers and, I hope, as a little talisman for the future.

Until now, I’ve thought of those chairs more in terms of how they served my grandfather: how he turned away from a colossal enterprise whose ill effects he had no control over and chose to live on a scale that gave him agency over his life. I hadn’t yet seen the parallels to my life or to this minute in time and the choices that lie ahead of us. Do we continue to aid and abet this harmful economy as it tries to reach higher and higher, beyond its safe boundaries, or do we call it quits, devise an entirely new way of living on this planet: small, connected to delight and marsh grasses, devoid of inexhaustible shopping and accumulating and moving and sorting endless amounts of stuff?

As some of you who have read the Nov. 21 blog know, I almost made this change once before in my life. Walking down Michigan Avenue in the early 1970’s in the warm sun of the day I was drawn to the shiny objects in every window. I wanted everything I saw: the platform boots and bell bottom jeans and fur coats. I had one of those aha! moments when I realized that if I stayed in the city, I would be too weak-kneed to resist the lure of all that glitter in the windows. I also believed that none of that would bring me happiness. I concluded in a flash that I’d have to leave the city or something terrible would happen to me: some version of losing my soul and becoming a member of a country club. I went home and talked to Bob and together we decided to leave, to pack everything up in a U-Haul truck and move as far away from consumption as one could get: to Maine.

It isn’t until writing this that I realize that by leaving the city I was doing what my grandfather had done. I didn’t think to cite him as the original source of inspiration for the idea that it was possible to leave the city and live a small and beautiful life.

Oh! the irony! Or maybe you could call it a test sent from the gods! We moved to Freeport, then a sleepy shoe factory town with one store, LLBean, where you could buy real things that outfitted you for real trips to the outdoors. (As opposed to what you can buy there now: fake outdoor things like red flannel shirts made in China and flown across the ocean that promise you can, for the price of the shirt, “Be an Outsider.”) Ten years after we moved, Freeport would become the shopping mecca of Maine and we would live .9 of a mile from its center.

By then, I’d failed the test. I lived in a happy consumer daze and didn’t wake up until practically yesterday. In the fifty years since we left Chicago, consumption in the USA has doubled.

But I think, this time, I have what I need to pass the test: a village. With the birth of FreeportCAN, I am surrounded by others who are challenging old cultural values and myths about growth, success, separation/independence, nature, consumerism. Neighbors and friends are, together, rewriting stories about living in a different way in relationship to food and buildings and transportation and land and each other. Soon we will sit around real campfires and mill around FreeportCAN’s Friday morning farmers’ market next to Town Hall comparing notes about where to buy local food and how to switch to a meat-free diet and what fun it is to take the Breeze to Portland instead of drive.

For this week’s action plan I have two offerings. The first is in the form of the book, “All We Can Save,” Edited by Ayana Elizabeth Johnson & Katherine K. Wilkenson. The editors describe the intent of the collection of essays this way:

“We hope this book can be a spark for connecting, learning together, deepening our resolve, and joyously finding our places in the mighty “we” that’s rising to secure a just and livable future.”

The second thing I have to offer is one of Pop-Pops’s tiny chairs. Next time you walk past a store with shiny things in the window and feel the pull to swerve through the door and buy that sparkling, totally unnecessary thing, think about Pop-Pop’s chairs, about a small and beautiful life filled with delight and connection, with things you make with your hands — and keep walking.

Next week, I anticipate I could be too tired from the packing and too distracted by the chaos and likely the sadness of letting go to be able send a Sunday morning blog. So don’t worry about me if it doesn’t appear. I will be back in two weeks.

Your post reminds me that each day brings the opportunity to start again. I wish you good things with your big move.

Love this! I think one of Pop-Pop’s tiny chairs should go to the Smithsonian along with your story! xo Susan